Constructing A Knowledge-driven and Data-driven Hybrid Decision Model for Etiological Diagnosis of Ventricular Tachycardia

-

摘要:目的

构建一个融合知识驱动和数据驱动的混合决策模型,并将其应用于室性心动过速的病因诊断。

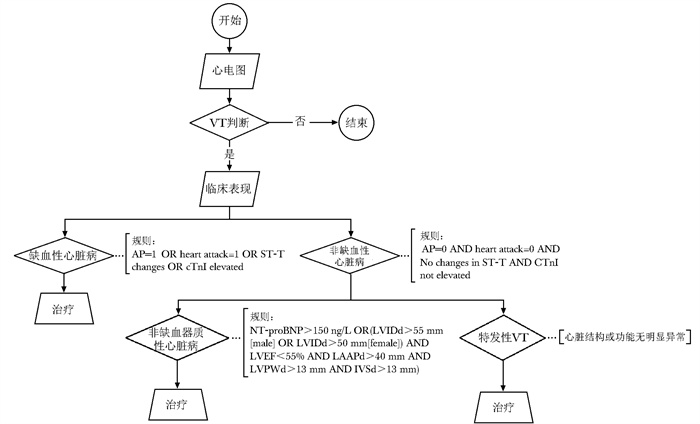

方法检索2018—2023年心律失常疾病领域的临床实践指南、专家共识和医学文献作为知识源,并回顾性收集2013—2023年中国医学科学院阜外医院室性心动过速(ventricular tachycardia, VT)患者的电子病历信息作为数据集。采用基于知识规则的方法构建临床路径作为知识驱动模型;基于真实世界数据构建VT病因诊断三分类机器学习模型,并选取其中的最佳模型作为数据驱动模型代表;以临床路径为基本框架,将机器学习模型以自定义运算符的形式嵌入临床路径的决策节点中,作为混合模型。评价上述3种模型的精确率、召回率和F1分数。

结果共纳入3部临床实践指南作为知识驱动模型的知识源;收集了1305条患者数据作为数据集,构建了5种机器学习模型,其中XGBoost模型最佳。混合模型采用知识驱动的决策思维,分别将XGBoost模型嵌入2层分类的决策节点中。3种模型的精确率、召回率和F1分数如下:知识驱动模型为80.4%、79.1%和79.7%;数据驱动模型分别为88.4%、88.5%和88.4%;混合模型分别为90.4%、90.2%和90.3%。

结论融合知识与数据驱动的混合模型展现出更高的准确性,且混合模型的所有决策结果均基于循证证据,这更接近临床医生的实际诊断思维。未来需更严格地验证混合模型广泛应用于医学领域的可行性。

Abstract:ObjectiveTo construct a hybrid decision-making model that integrates knowledge-driven and data-driven approaches, and to apply it to the etiological diagnosis of ventricular tachycardia (VT).

MethodsClinical practice guidelines, expert consensus documents, and medical literature in the field of arrhythmia diseases from 2018 to 2023 were retrieved as knowledge sources. Retrospective electronic medical record data of VT patients from Fuwai Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, from 2013 to 2023 were collected as the dataset. A knowledge-driven model was constructed using a knowledge-rule-based approach to establish clinical pathways. A three-class machine learning model for VT etiology diagnosis was developed based on real-world data, and the best-performing model was selected as the representative of the data-driven approach. The machine learning model was embedded into the decision nodes of the clinical pathway in the form of custom operators, forming the hybrid model. The precision, recall, and F1 score of the three models were evaluated.

ResultsThree clinical practice guidelines were included as knowledge sources for the knowledge-driven model. A total of 1305 patient records were collected as the dataset, and five machine learning models were constructed, with the XGBoost model performing the best. The hybrid model adopted a knowledge-driven decision-making framework, embedding the XGBoost model into the decision nodes of a two-level classification. The precision, recall, and F1 scores of the three models were as follows: the knowledge-driven model achieved 80.4%, 79.1%, and 79.7%; the data-driven model achieved 88.4%, 88.5%, and 88.4%; and the hybrid model achieved 90.4%, 90.2%, and 90.3%.

ConclusionsThe hybrid model integrating knowledge-driven and data-driven approaches demonstrated higher accuracy, and all its decision outcomes were based on evidence-based practices, aligning more closely with the actual diagnostic reasoning of clinicians. Further rigorous validation is needed to assess the feasibility of widely applying the hybrid model in the medical field.

-

Keywords:

- ventricular tachycardia /

- knowledge-driven /

- data-driven /

- hybrid model /

- decision-making

-

1. 历史沿革

早在1908年,Oskar Ehrhardt首次描述了胰腺节段切除[1]。1910年,美国的Finney教授[2]对一例囊性肿瘤患者实施了胰颈节段切除,但是切除后未行胰腺功能重建,采用胰腺近-远断端直接吻合,术后患者出现严重胰瘘,持续3个月方愈合。1950年,日本的Honjyo对两例胃癌并胰腺颈部浸润的患者实施了胃切除及胰腺中段切除,但并未进行胰腺功能重建,而是用大网膜将远端胰腺残端包裹并缝合[1]。Guillemin和Bessot[3]在1957年对1例慢性胰腺炎患者实施手术的过程中,无意中导致胰颈部横断,作为补救措施,进行了“Ω”形胰腺空肠袢吻合术。随后,Letton和Wilson[4]在1959年对2例胰腺外伤胰颈横断的患者实施了近端胰腺残端缝合及远端胰腺空肠Roux-en-Y吻合术(pancreaticojejunostomy,PJ)。但这些均不是标准或治疗意义的胰腺中段切除术。直至1982年,胰腺中段切除术(central pancreatectomy, CP)才首次作为一种治疗手段,用于胰腺肿瘤的治疗。Dagradi和Serio有计划地为一例胰岛素瘤患者进行了CP术,并详细介绍了切除和胰肠吻合的技术、技巧,成为CP发展史上的里程碑事件。随后,Iacono等[1]将该术式向世界范围推广。因此,CP也被称为“Dagradi-Serio-Iacono术”。尽管CP能够保留更多的胰腺组织及内外分泌功能,但由于手术相对复杂,并发症发生率高,直到20世纪末才被广泛接受并逐渐在临床展开。

微创技术能够减轻患者痛苦,降低围手术期并发症,缩短住院时间,加速患者康复。多种胰腺微创手术,包括剜除术、胰体尾切除术,已经常规在临床开展。但CP术比较复杂,既涉及胰腺切除、重建,也要面对复杂的解剖结构(邻近门静脉、肠系膜上动静脉、肝总动脉、脾动/静脉等重要血管),微创手术学习曲线较长,发展和推广亦缓慢。Baca和Bokan[5]在2003年首次实施了腹腔镜下胰腺中段切除术(laparoscopic central pancreatectomy, LCP),2004年Giulianotti等[6]完成第一例机器人辅助CP术。目前,LCP在大的胰腺中心已经成为常规术式。文献报道的LCP和机器人胰腺中段切除术(robotic central pancreatectomy,RCP)术后胰瘘发生率分别为0~100%和20%~71.4%[7]。与开腹胰腺中段切除术(open central pancreatectomy,OCP)组相比,LCP组术中出血显著减少,禁食时间缩短,排气时间提前,远期生活质量更高[8]。与开腹组相比,RCP术中出血量、输血率及术后住院时间均具有优势;相比腹腔镜技术,机器人手术系统具有更高分辨率的立体视野以及灵巧稳定的器械操作臂,在胰腺功能重建方面更有优势[9-10],因此,有学者认为CP是机器人胰腺外科的最佳适应证[7]。

2. 适应证及禁忌证

对于有经验的外科医师,LCP与OCP的适应证和禁忌证相同。适应证[11]主要包括:肿瘤直径 > 5 cm(亦有报道对直径≥5 cm的病变可实施CP[12]),深入胰腺实质,单纯剜除可能损伤主胰管的胰颈或胰体近端良性、低度恶性肿瘤(神经内分泌肿瘤、浆液性/粘液性囊腺瘤、实性假乳头状瘤)以及孤立转移灶[13];不具备剜除指征的非肿瘤囊性病变,如淋巴上皮囊肿、皮样囊肿、包虫囊等;慢性胰腺炎伴有局灶性胰管狭窄或结石。禁忌证包括:胰腺原发恶性肿瘤;胰腺弥漫性炎症或胰体尾部萎缩;预计中段胰腺切除后无法保留至少5 cm的远端胰腺;血管变异(胰颈体尾部主要由胰横动脉供应,切除中段胰腺后,胰体尾缺血坏死可能)[14-15]。对于 < 3 cm的胰腺神经内分泌肿瘤,局部切除的价值尚存在争议,部分观点认为应行规则胰腺切除联合区域淋巴结清扫。

CP术用于治疗胰腺导管内乳头状黏液性肿瘤(intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm,IPMN)尚存在争议,Sauvanet等[16]发现,与其他良性或低度恶性肿瘤相比,IPMN患者存在更高的术后并发症、糖尿病及肿瘤复发率,因此不建议对IPMN患者实施CP术。而DiNorcia等[17]认为CP术可用于治疗IPMN,但应常规行术中冰冻切片,获取病理诊断及切缘信息,确保为非侵袭性病变且切缘阴性。若术后病理证实存在重度不典型增生,则应密切随访。

3. 术后并发症

CP术往往要面对柔软的胰腺、细胰管及两个胰腺创面,因此存在较高的围手术期并发症及更长的术后住院时间。Goudard等[18]报道100例CP术,并发症发生率为72%, Clavien-Dindo Ⅲ~Ⅳ级并发症发生率为15%,再手术率为6%, 死亡率为3%。胰瘘是最主要的并发症,Goudard等[18]报道的胰瘘发生率为63%,其中B或C级胰瘘占44%。Santangelo等[11]对1992至2015年发表的关于CP的文献进行了系统回顾,胰瘘发生率为0~65%,高于标准的胰腺切除[胰十二指肠切除术(0~25%)、胰体尾切除(2%~32%)]。但随着国际胰瘘研究小组发布新的胰瘘诊断及分级标准[19],部分C级胰瘘可能降级为B级胰瘘[20],CP术后胰瘘情况值得进一步评估。

胰腺内外分泌功能不全,是胰腺切除术后最常见的远期并发症。CP由于保存了更多的胰腺组织,此类并发症发生率低于胰体尾切除术。Iacono等[21]对1988至2010年报道的963例CP病例进行了Meta分析,CP术后内外分泌功能不全的发生率分别为5.5%和11.9%,显著低于胰体尾切除术(23.6%和19.1%)。Crippa等[22]报道的100例CP术,中位随访54个月,CP组新发内外分泌功能不全的发生率显著低于胰体尾切除组(4%比38%和5%比15.6%)。

4. 腹腔镜下胰腺中段切除术的手术技巧

CP术包括切除和重建两个过程。对于腔镜下的操作过程,应重点关注以下几方面处理技巧。

4.1 小网膜囊内空间的建立

打开胃结肠韧带时,应该有较充分的显露空间,以横结肠自然坠落,远端胃可自由翻起为宜,以便于解剖门静脉(portal vein,PV)、肠系膜上静脉(superior mesenteric vein,SMV)及消化道重建,但也应避免过大范围游离,注意保护胃网膜左血管及胃短血管,一旦脾血管因故结扎切断,仍可通过脾周循环保持脾血供和回流,避免脾切除。

4.2 肠系膜上静脉显露

于胰腺下缘解剖显露SMV时,应特别注意胰腺通往SMV的静脉属支,这类血管纤细,稍有牵拉即可造成撕裂、出血,因此应仔细解剖并处理。采用Hemolok或钛夹夹闭,既影响胰后隧道的建立,也可能在进一步操作时脱落、出血。笔者建议采用Prolene线缝扎或双极电凝炭化。对于难以控制的出血,可用纱条或明胶海绵暂时压迫止血,待标本移除后,再缝扎血管残端或破口。

4.3 胰后隧道的建立

胰颈后方通常无静脉属支汇入门静脉,且组织层次较疏松,通过钝性分离即可成功贯穿胰后隧道。但对于胰腺或肿瘤与门静脉粘连的病例应避免盲目钝性分离,勉强完成该操作可能导致门静脉撕裂而大出血。建议直视下分离,逐步贯穿隧道。如果在建立胰后隧道的过程中发生门静脉出血,可用纱条或明胶海绵暂时压迫,离断胰腺后再用Prolene线修补。困难病例可先切断胰腺,再进一步分离胰腺或肿瘤与门静脉粘连部位。

4.4 肝总动脉的保护

术中可先于胰腺上缘解剖出肝总动脉,并悬吊、提起,避免用腔镜下切割闭合器切断胰腺时误伤肝总动脉。

4.5 近端胰腺断面的处理

既可采用切割闭合器也可采用超声刀切断胰腺,两种方式对于术后胰瘘发生率并无统计学差异[23-24]。对于使用切割闭合器的患者,应结合胰腺质地、厚度,选用合适的钉匣,避免过度压榨导致胰腺坏死。如果通过超声刀切断胰腺,应仔细寻找近端主胰管并缝扎,可能降低胰瘘发生率。如果无法确认近端主胰管,则可用Prolene线缝合断面,但应该避免过度缝合,导致胰腺坏死、胰瘘及出血。也有报道胰腺近、远端分别与空肠行“Ω”式吻合。

4.6 远端胰腺功能重建

在切断胰腺时应该明确主胰管位置,避免烧灼、闭塞主胰管,为胰腺功能重建增加困难。对于远端胰腺功能重建,目前主要有PJ及胰胃吻合(pancreaticogastrostomy,PG),也有报道CP术后不行胰腺功能重建亦能获得较好的预后[25]。美国、日本、法国等学者常采用PG吻合[21],但对于PG的价值目前尚存争议。一方面,基于随机对照临床试验的Meta分析认为,PD术后PG组的胰瘘发生率显著低于PJ组[26],且PG技术简单,在微创时代可能有更大的应用空间[27]。另一方面,PG存在的一些缺点可能影响患者长期预后,比如胰酶与胃酸的中和作用,可能影响消化功能;酸性胃液可能导致胰腺残端坏死、出血或纤维化;其他如胰管堵塞,远端胰腺萎缩,内外分泌功能障碍等[28]。由于接受CP的患者主要为胰腺良性或低度恶性肿瘤患者,术后可长期存活,PG术可能降低患者的远期生活质量。尽管对于PG的应用尚存争议,但PG应用于CP较胰十二指肠切除术仍有较大优势,因其不破坏消化道原有连续性,并且患者胰头和钩突可完整保留,即使远端胰管堵塞,也不影响其内外分泌功能。而且操作简便(均在结肠上区),并发症发生率低。另外IPMN患者还可通过内镜下检查远端胰腺和胰管情况,具有一定优势[29]。因此,合理灵活选择是关键。

PJ仍是目前的主流吻合方式[21],套入式吻合及导管-黏膜吻合是主要的吻合方法。对于扩张的胰管,导管-黏膜吻合已经得到广泛接受和认可,与套入法相比,可显著降低胰瘘发生率[30-31]。而对细胰管或软胰腺,其价值仍存在争议。一些Meta分析及前瞻性研究发现,虽然两种吻合方法的胰瘘发生率并无显著差异,但导管-黏膜吻合有增加胰瘘发生率的趋势[32-34]。由于导管-黏膜吻合对手术技巧要求比较高,而且对于细胰管(> 3 mm)很难做到精确吻合,从而导致吻合口狭窄或闭合,因此有学者不推荐腔镜下完成此吻合。笔者认为,充分发挥腹腔镜高清、放大及角度优势,并辅以合理的手术技巧,可在腔镜下完成高质量的细导管-黏膜吻合。本中心的经验是,采用压榨法(clamp-crushing technique)切断远端胰腺,这样有利于发现主胰管,且可保证3~5 mm的胰管外露。切断胰腺后,继续向远端游离胰腺1~2 cm,有利于吻合时牵拉胰腺,使胰腺断面正对术者的视野。吻合时,采用一根PDS-Ⅱ缝线连续缝合导管-黏膜,逐一收紧每针缝线,能够使吻合口外翻,以获取更好的缝合视野。当然,与套入法相比,可能学习曲线更长,耗时更多。总之,胰腺功能重建应结合胰管直径、胰腺质地及术者经验,选用最为熟悉的吻合方式。

5. 小结与展望

CP主要用于胰腺颈部良性及低度恶性病变,尽管围手术期并发症高于标准胰腺切除,但其基本保存了消化道完整性,保留了更多的胰腺组织及脾脏,显著降低了长期并发症、提高了患者生活质量。微创外科的发展,引起了胰腺手术的变革,与传统开放手术相比,LCP加速了术后康复,只要把握好手术适应证,将有更大的使用空间及推广价值,最终使患者获益。

作者贡献:王敏负责研究设计、数据分析及论文撰写;胡兆负责数据收集、论文修订;徐晓巍、郑思负责论文修订;李姣、姚焰提供研究思路,负责论文修订。利益冲突:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突 -

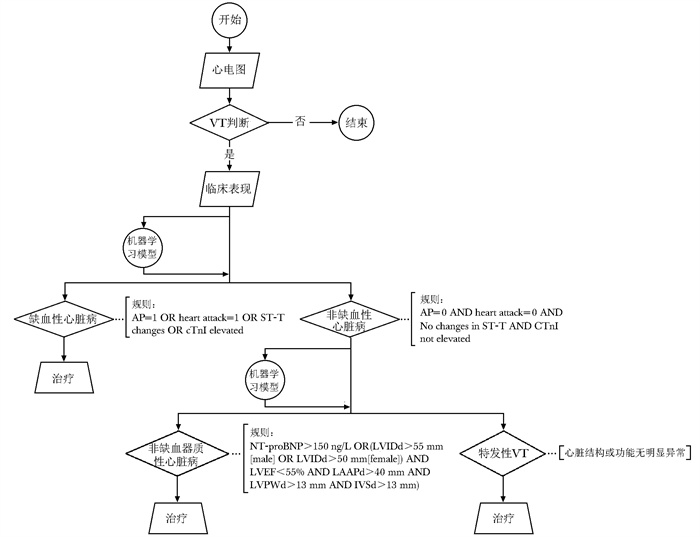

图 1 基于知识驱动的临床路径

VT(ventricular tachycardia): 室性心动过速;AP(angina pectoris):心绞痛;cTnI(cardiac troponin I):肌钙蛋白I;NT-proBNP(N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide):N末端B型钠尿肽前体;LVIDd(left ventricular internal diameter in diastole):左心室舒张期内径;LVEF(left ventricular ejection fraction):左心室射血分数;LAAPd(left atrial anteroposterior diameter):左心房前后径;LVPWd(left ventricular posterior wall thickness): 左心室后壁厚度;IVSd(interventricular septum thickness in diastole):室间隔厚度

Figure 1. Knowledge-driven clinical pathway

图 2 基于混合驱动的临床路径

VT、AP、cTnI、NT-proBNP、LVIDd、LVEF、LAAPd、LVPWd、IVSd:同图 1

Figure 2. Hybrid-driven clinical pathway

表 1 5种机器学习模型性能比较(%)

Table 1 Comparison of five machine learning model performances(%)

模型 缺血性心脏病 非缺血器质性心脏病 特发性VT 整体 精确率 召回率 F1分数 精确率 召回率 F1分数 精确率 召回率 F1分数 精确率 召回率 F1分数 Logistic Regression 73.5 80.0 76.6 56.2 36.0 43.9 76.4 82.4 82.4 70.9 72.2 71.0 Random Forest 88.4 88.4 88.4 74.6 70.7 72.6 93.4 97.1 95.2 87.1 87.2 87.1 XGBoost 87.9 91.6 89.7 80.9 73.3 76.9 95.0 93.1 94.1 88.4 88.5 88.4 LightGBM 87.9 91.2 89.5 81.5 70.7 75.7 93.3 95.1 94.2 88.1 88.3 88.1 SVM 84.0 87.9 85.9 82.3 68.0 74.5 84.8 87.3 86.0 83.9 83.9 83.7 VT: 同图 1 -

[1] Bal M, Amasyali M F, Sever H, et al. Performance evaluation of the machine learning algorithms used in inference mechanism of a medical decision support system[J]. ScientificWorldJournal, 2014, 2014: 137896.

[2] 陆瑶, 刘佳宁, 王冕, 等. 人工智能在医患共同决策中的应用[J]. 协和医学杂志, 2024, 15(3): 661-667. DOI: 10.12290/xhyxzz.2023-0209 Lu Y, Liu J N, Wang M, et al. Artificial intelligence in shared decision making[J]. Med J PUMCH, 2024, 15(3): 661-667. DOI: 10.12290/xhyxzz.2023-0209

[3] Hak F, Guimarães T, Santos M. Towards effective clinical decision support systems: a systematic review[J]. PLoS One, 2022, 17(8): e0272846. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0272846

[4] 郑锐, 于广军. 临床辅助决策支持系统研究综述[J]. 中国数字医学, 2023, 18(11): 70-77. Zheng R, Yu G J. A review of clinical assisted decision-making support system[J]. Chin Digit Med, 2023, 18(11): 70-77.

[5] 张山, 崔薇, 吴瑛. 以智能化谵妄护理临床决策辅助支持系统为例探讨规则驱动的临床护理决策支持系统的基本组成[J]. 护理研究, 2022, 36(24): 4464-4468. DOI: 10.12102/j.issn.1009-6493.2022.24.028 Zhang S, Cui W, Wu Y. Basic components of a rule-driven clinical nursing decision support system: an example of an intelligent delirium nursing clinical decision aid support system[J]. Chin Nurs Res, 2022, 36(24): 4464-4468. DOI: 10.12102/j.issn.1009-6493.2022.24.028

[6] 周祎灵, 石清阳, 陈向阳, 等. 本体在糖尿病临床决策支持系统中的应用[J]. 四川大学学报(医学版), 2023, 54(1): 208-216. Zhou Y L, Shi Q Y, Chen X Y, et al. Ontologies applied in clinical decision support systems for diabetes[J]. J Sichuan Univ(Med Sci), 2023, 54(1): 208-216.

[7] Rajula H S R, Verlato G, Manchia M, et al. Comparison of conventional statistical methods with machine learning in medicine: diagnosis, drug development, and treatment[J]. Medicina (Kaunas), 2020, 56(9): 455. DOI: 10.3390/medicina56090455

[8] Tutun S, Johnson M E, Ahmed A, et al. An AI-based decision support system for predicting mental health disorders[J]. Inf Syst Front, 2023, 25(3): 1261-1276. DOI: 10.1007/s10796-022-10282-5

[9] 王敏, 胡兆, 徐晓巍, 等. 面向心律失常疾病的临床决策支持系统交互性研究与实现[J]. 医学信息学杂志, 2024, 45(4): 70-77. Wang M, Hu Z, Xu X W, et al. Research and implementation of interactivity in the clinical decision support system for arrhythmia diseases[J]. J Med Intell, 2024, 45(4): 70-77.

[10] 龚欢欢, 柯晓伟, 王爱民, 等. 可解释机器学习模型预测心脏骤停患者院内死亡风险: 基于MIMIC-Ⅳ 2.0数据库[J]. 协和医学杂志, 2023, 14(3): 528-535. DOI: 10.12290/xhyxzz.2022-0733 Gong H H, Ke X W, Wang A M, et al. An interpretable machine learning model for predicting in-hospital death risk in patients with cardiac arrest: based on US medical information mart for intensive care database Ⅳ2.0[J]. Med J PUMCH, 2023, 14(3): 528-535. DOI: 10.12290/xhyxzz.2022-0733

[11] Trottet C, Vogels T, Keitel K, et al. Modular Clinical Decision Support Networks (MoDN)-updatable, interpretable, and portable predictions for evolving clinical environments[J]. PLOS Digital Health, 2023, 2(7): e0000108. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pdig.0000108

[12] Buschmeyer K, Hatfield S, Zenner J. Psychological assessment of AI-based decision support systems: tool development and expected benefits[J]. Front Artif Intell, 2023, 6: 1249322. DOI: 10.3389/frai.2023.1249322

[13] Phillips-Wren G, Adya M. Decision making under stress: the role of information overload, time pressure, complexity, and uncertainty[J]. J Decis Syst, 2020, 29(S1): 213-225.

[14] Rosen S, Saban M. Can ChatGPT assist with the initial triage? A case study of stroke in young females[J]. Int Emerg Nurs, 2023, 70: 101340. DOI: 10.1016/j.ienj.2023.101340

[15] Rosen S, Saban M. Evaluating the reliability of ChatGPT as a tool for imaging test referral: a comparative study with a clinical decision support system[J]. Eur Radiol, 2024, 34(5): 2826-2837.

[16] Hussain M, Afzal M, Ali T, et al. Data-driven knowledge acquisition, validation, and transformation into HL7 Arden Syntax[J]. Artif Intell Med, 2018, 92: 51-70. DOI: 10.1016/j.artmed.2015.09.008

[17] Brown D, Aldea A, Harrison R, et al. Temporal case-based reasoning for type 1 diabetes mellitus bolus insulin decision support[J]. Artif Intell Med, 2018, 85: 28-42. DOI: 10.1016/j.artmed.2017.09.007

[18] Jiao Y, Zhang Z, Zhang T, et al. Development of an artificial intelligence diagnostic model based on dynamic uncertain causality graph for the differential diagnosis of dyspnea[J]. Front Med, 2020, 14(4): 488-497. DOI: 10.1007/s11684-020-0762-0

[19] Vilhena J, Rosário Martins M, Vicente H, et al. An integrated soft computing approach to Hughes syndrome risk assessment[J]. J Med Syst, 2017, 41(3): 40. DOI: 10.1007/s10916-017-0688-5

[20] Roberts-Thomson K C, Lau D H, Sanders P. The diagnosis and management of ventricular arrhythmias[J]. Nat Rev Cardiol, 2011, 8(6): 311-321. DOI: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.15

[21] Hu Z, Wang M, Zheng S, et al. Clinical decision support requirements for ventricular tachycardia diagnosis within the frameworks of knowledge and practice: survey study[J]. JMIR Hum Factors, 2024, 11: e55802. DOI: 10.2196/55802

[22] 覃露, 徐晓巍, 丁玲玲, 等. 面向决策支持的临床指南知识表示方法研究[J]. 中华医学图书情报杂志, 2020, 29(2): 1-8. Qin L, Xu X W, Ding L L, et al. Knowledge representation methods of clinical guidelines for clinical decision support system[J]. Chin J Med Libr Inf Sci, 2020, 29(2): 1-8.

[23] 闵令通, 段会龙, 吕旭东. 基于openEHR的医疗信息建模方法[J]. 中华医学图书情报杂志, 2018, 27(3): 1-4. Min L T, Duan H L, Lyu X D. Medical information modeling based on openEHR[J]. Chin J Med Libr Inf Sci, 2018, 27(3): 1-4.

[24] Pedersen C T, Kay G N, Kalman J, et al. EHRA/HRS/APHRS expert consensus on ventricular arrhythmias[J]. Europace, 2014, 16(9): 1257-1283. DOI: 10.1093/europace/euu194

[25] European Heart Rhythm Association, Heart Rhythm Society. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for practice guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death)[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2006, 48(5): e247-e346. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.010

[26] Zeppenfeld K, Tfelt-Hansen J, de Riva M, et al. 2022 ESC guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death[J]. Eur Heart J, 2022, 43(40): 3997-4126.

[27] Breiman L. Random forests[J]. Mach Learn, 2001, 45(1): 5-32.

[28] Chen T Q, Guestrin C. XGBoost: a scalable tree boosting system[C]//Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. New York: Association for Computing Machinery, 2016: 785-794.

[29] Ke G L, Meng Q, Finley T, et al. LightGBM: a highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree[C]//Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. Red Hook: Curran Associates Inc., 2017: 3149-3157.

[30] Noble W S. What is a support vector machine?[J]. Nat Biotechnol, 2006, 24(12): 1565-1567.

[31] Boeddinghaus J, Doudesis D, Lopez-Ayala P, et al. Machine learning for myocardial infarction compared with guideline-recommended diagnostic pathways[J]. Circulation, 2024, 149(14): 1090-1101.

[32] Zhao K K, Zhu Y J, Chen X Y, et al. Machine learning in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: nonlinear model from clinical and CMR features predicting cardiovascular events[J]. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging, 2024, 17(8): 880-893.

[33] D'Ascenzo F, De Filippo O, Gallone G, et al. Machine learning-based prediction of adverse events following an acute coronary syndrome (PRAISE): a modelling study of pooled datasets[J]. Lancet, 2021, 397(10270): 199-207.

[34] Sutton R T, Pincock D, Baumgart D C, et al. An overview of clinical decision support systems: benefits, risks, and strategies for success[J]. NPJ Digit Med, 2020, 3: 17.

[35] Khairat S, Marc D, Crosby W, et al. Reasons for physicians not adopting clinical decision support systems: critical analysis[J]. JMIR Med Inform, 2018, 6(2): e24.

[36] Shoaip N, El-Sappagh S, Abuhmed T, et al. A dynamic fuzzy rule-based inference system using fuzzy inference with semantic reasoning[J]. Sci Rep, 2024, 14(1): 4275.

[37] 张知非, 杨郑鑫, 黄运有, 等. 医学大数据与人工智能标准体系: 现状、机遇与挑战[J]. 协和医学杂志, 2021, 12(5): 614-620. DOI: 10.12290/xhyxzz.2021-0472 Zhang Z F, Yang Z X, Huang Y Y, et al. Big medical data and medical AI standards: status quo, opportunities and challenges[J]. Med J PUMCH, 2021, 12(5): 614-620. DOI: 10.12290/xhyxzz.2021-0472

[38] Tjoa E, Guan C T. A survey on explainable artificial intelligence (XAI): toward medical XAI[J]. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst, 2021, 32(11): 4793-4813.

[39] Zheng J X, Li X, Zhu J, et al. Interpretable machine learning for predicting chronic kidney disease progression risk[J]. Digit Health, 2024, 10: 20552076231224225.

[40] Fan F L, Xiong J J, Li M Z, et al. On interpretability of artificial neural networks: a survey[J]. IEEE Trans Radiat Plasma Med Sci, 2021, 5(6): 741-760.

[41] Park S, Lee S J, Weiss E, et al. Intra- and inter-fractional variation prediction of lung tumors using fuzzy deep learning[J]. IEEE J Transl Eng Health Med, 2016, 4: 4300112.

[42] Lobach D F, Johns E B, Halpenny B, et al. Increasing complexity in rule-based clinical decision support: the symptom assessment and management intervention[J]. JMIR Med Inform, 2016, 4(4): e36.

-

期刊类型引用(1)

1. 刘玉文,张丽梅,王永丽,徐小梅,母亚丹,杨志杰,杨树婷,罗凤云. 老年多学科团队服务对共病伴营养不良老年患者的疗效分析. 昆明医科大学学报. 2024(12): 81-87 .  百度学术

百度学术

其他类型引用(0)

作者投稿

作者投稿 专家审稿

专家审稿 编辑办公

编辑办公 邮件订阅

邮件订阅 RSS

RSS

下载:

下载: