The Role of Visceral Adipose Tissue in the Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Crohn's Disease

-

摘要: 克罗恩病(Crohn's disease,CD)是一种慢性炎性肉芽肿性疾病,多发于末端回肠和临近结肠,呈节段性分布。CD肠道病变的机制尚不完全明确,与遗传、免疫和环境等多种因素有关。脂肪组织在CD的发病中发挥重要作用,最新研究发现内脏脂肪组织(visceral adipose tissue,VAT),特别是其肠系膜成分,亦称为爬行脂肪,可通过免疫调节特性影响CD进程。本文主要综述VAT在CD发病、诊断及治疗中的研究进展,以期为临床诊疗提供理论依据。Abstract: Crohn's disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory granulomatous disease, which usually occurs at the end of the ileum and adjacent colon with segmental distribution. The pathogenesis of CD's intestinal lesions is not completely clear, which is related to multiple factors such as heredity, immunity, and environment. Adipose tissue plays an important role in the pathogenesis of CD. Recently, it has been found that visceral adipose tissue (VAT), especially its mesenteric component, i.e. creeping fat, has an impact on the disease course through its immunomodulatory properties. This paper reviews the research progress of VAT in the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of CD, in order to provide theoretical basis for clinicians.

-

Keywords:

- visceral adipose tissue /

- creeping fat /

- Crohn's disease /

- adipokines

-

研究认为身体成分与许多健康问题和疾病之间都有密切的关系,如肥胖症、糖尿病、代谢综合征、高血压、高脂血症、心血管疾病等[1-5]。青少年阶段是身体发育的重要时期,研究青少年阶段的身体成分有助于了解人体的体质、健康和发育程度,以利于将青少年的体重控制在一定范围内,使体重中脂肪含量和水分含量都处于比较适宜的比例,以降低与肥胖有关的各种疾病的发生率并减少其危害,增进身体健康。

中国是一个多民族国家,许多少数民族都保持着独特的生活方式和饮食习惯,并居住在特殊的生活环境中。大多数藏族青少年都居住于高海拔地区,与平原地区相比,高海拔地区空气中氧分压较低,可能对人体产生一些影响,而且藏族青少年的饮食习惯、生活习俗等许多方面都与汉族不尽一致,这些都可能导致藏族和汉族青少年的身体发育情况不同步。对于生活在高海拔地区的藏族青少年的身体成分研究,甚至对于藏族青少年和汉族青少年身体成分比较的研究目前鲜有报道。本研究旨在通过大规模的人群调查探讨藏族和汉族青少年身体成分的差异,为不同民族青少年身体发育状况研究提供依据。

对象和方法

研究对象

样本来源于人体生理常数数据库扩大人群调查于2007年在四川省进行的中国正常人群生理、心理常数调查,本次调查采用分层二阶段整群抽样的原则。以省作为主层,主层下分为城市和农村2个分层,每个分层各整群抽取若干个村或社区,以抽到的社区和村中所有符合条件的正常人群作为该研究的调查对象。受试者的纳入标准为:年龄范围10~18岁;签署知情同意。排除标准为:(1)患有心、肺、肝、脑、肾等主要脏器疾病者;(2)身体发育异常者;(3)患有急性病或在最近15 d内有高热、感冒者。根据纳入和排除标准,所有符合条件的受试者按照连续入组的方式参与本调查。本研究的藏族受试者来自海拔3000 m以上的四川省阿坝藏族羌族自治州东北部的松潘县。研究经中国医学科学院基础医学研究所伦理委员会批准。

身体成分测量

用美国Biodynamics Corporation生产的Biodynamics BI-310身体成分分析仪进行身体成分测定,利用人体对分析仪发出的无害小电流所产生的阻抗(生物阻抗),来计算人体内各种成分所占的比例及重量。受试者测定前24 h内不能喝酒,测定前4 h禁食和停止运动,测定前不能服用利尿剂。受试者仰卧,身体放松,尽量将双手离开身体两侧15 cm;双脚分开,避免接触,双脚之间距离不少于15 cm。充分暴露右侧踝部和手腕,避开尼龙织物。将一对电极的第一个放在靠近腕部,电极边缘位于手腕的皱褶处,第二个放在同一手背面中央,靠近掌指关节处;将另一对电极的第一个放在靠近踝部,电极边缘位于脚跟的皱褶处,第二个放在同一脚的脚背中央,靠近脚趾根部。将仪器与感应线、电极连接。检测指标包括:基础代谢率、脂肪重量、脂肪百分比、瘦体重(去脂体重)、身体总水分和电阻抗值。体重指数(body mass index,BMI) =体重/身高2,脂肪体重指数(fat mass index,FMI) =脂肪体重/身高2,去脂体重指数(fat-free mass index,FFMI) =去脂体重/身高2。

质量控制

购买同一品牌同一型号的检测仪器。在测试前,对几台仪器进行比对,尽量减少仪器之间的测量误差。体质检测人员均按培训手册进行统一培训,人员固定;每一项调查和关键步骤完成者均需进行操作人员签名,以备监督和备案;所有仪器每天进行校正,并在工作记录中登记备案;每日完成的调查表均在当日进行抽查,检查其填写质量,发现问题及时纠正。

数据库建立和统计学处理

采用EP l3.02软件编制数据录入程序,进行数据录入与管理,为保证数据的准确性,由两个数据管理员独立进行双份录入并校对。录入完成后,按调查内容分类组织专人对数据进行再核查,根据统一的核查原则,将发现的可疑记录反馈,与原始表格核对。所有统计计算用SAS 9.2统计分析软件进行,统计检验用双侧检验。服从正态分布的定量资料以均数和标准差表示,不服从正态分布的定量资料用中位数和下四分位数(Q1)、上四分位数(Q3)表示,分类变量用例数和百分数进行描述。服从正态分布的定量资料的比较用t检验,不服从正态分布的定量资料的比较用Wilcoxon秩和检验。以P≤0.05为差异有统计学意义。

结果

人口学特征

75名青少年因患有先天性心脏病等主要脏器疾病或近期出现感冒、发烧而被排除本次调查,共1473名年龄在10~18岁的青少年完成身体成分检测,除外非汉族和藏族受试者33名,最终共1440名受试者纳入分析,其中汉族733名,藏族707名。733名汉族受试者中,男性369名,平均年龄(13.8±2.3)岁,女性364名,平均年龄(13.8±2.5)岁;707名藏族受试者中,男性309名,平均年龄(14.1±2.2)岁,女性398名,平均年龄(13.8±2.1)岁。两民族受试者的性别构成和平均年龄基本均衡。

汉族和藏族青少年身体成分指标比较

比较两民族青少年的身体测量指标,结果显示藏族青少年的平均身高略低于汉族(男性:150.06 cm比154.03 cm,P<0.001;女性:147.28 cm比151.06 cm,P<0.001)。藏族青少年男性的平均体重和BMI与汉族差异均无统计学意义;藏族青少年女性的平均体重和汉族差异无统计学意义,但其BMI略大(19.33 kg/m2比18.46 kg/m2,P<0.001)。受试者BMI范围为12.81~ 28.93 kg/m2,有45名受试者BMI小于15 kg/m2。比较两民族青少年的身体成分构成,结果显示藏族青少年男性和女性的瘦体重都显著低于汉族青少年(男性:35.20 kg比39.05 kg,P<0.001;女性:32.25 kg比35.60 kg,P<0.001),而脂肪体重明显高于汉族青少年(男性:5.90 kg比3.40 kg,P<0.001;女性:9.65 kg比7.25 kg,P<0.001),故藏族青少年男性的脂肪百分比比汉族高6.62%,藏族青少年女性的脂肪百分比比汉族高6.42%,差异均有统计学意义(P<0.001)。

藏族青少年的瘦体重明显低于汉族,其身体总水分含量及含水量占体重百分比也显著低于汉族青少年,藏族青少年的FMI显著高于汉族青少年,但FFMI显著较低。此外,藏族青少年的代谢率也显著低于汉族青少年,但电阻抗值高于汉族青少年。水分占瘦体重百分比在两民族青少年间差异有统计学意义,但差值较小(表 1)。

表 1 藏族和汉族青少年身体成分指标比较指标 民族 男性 女性 n (x±s)/M(Q1,Q3) t/Z值 P值 n (x±s)/M(Q1,Q3) t/Z值 P值 身高(cm) 藏族 307 150.06±14.45 3.733 <0.001 394 147.28±10.60 5.204 <0.001 汉族 369 154.03±12.96 363 151.06±9.41 体重(kg) 藏族 309 42.52±10.85 1.748 0.081 398 42.56±10.02 0.005 0.996 汉族 369 43.96±10.48 364 42.55±9.07 BMI(kg/m2) 藏族 307 18.54±1.86 1.484 0.149 394 19.33±2.60 4.668 <0.001 汉族 369 18.29±2.48 363 18.46±2.52 身体总水分(kg) 藏族 309 25.85±7.15 4.901 <0.001 393 23.57±3.90 6.088 <0.001 汉族 369 28.53± 7.05 398 25.27±3.80 含水量占体重百分比(%) 藏族 308 60.51±4.07 12.050 <0.001 362 56.47±5.35 9.572 <0.001 汉族 368 64.86±5.29 398 60.34±5.80 水分占瘦体重百分比(%) 藏族 309 71.35±1.81 5.507 <0.001 362 73.57±3.40 4.211 <0.001 汉族 368 72.15±1.92 398 72.64±2.73 代谢率(kJ) 藏族 309 4613.07±1336.20 4.173 <0.001 362 4117.85±842.49 5.574 <0.001 汉族 369 5030.93±1266.16 398 4448.47±790.15 电阻抗值(Ω) 藏族 309 2614.12±90.85 7.975 <0.001 364 686.21±75.51 11.153 <0.001 汉族 368 560.83±81.26 394 628.74±66.30 FFMI(kg/m2) 藏族 307 15.75±1.94 4.202 <0.001 364 14.71± 1.53 4.528 <0.001 汉族 368 16.39±2.00 394 15.22± 1.56 FMI(kg/m2) 藏族 306 2.70(2.04, 3.52) 10.212 <0.001 363 4.35(3.50, 5.56) 11.160 <0.001 汉族 368 1.46(0.62, 2.62) 394 3.08(2.14, 4.30) 瘦体重(kg) 藏族 309 35.20(27.15, 45.00) 4.179 <0.001 363 32.25(27.18, 37.03) 5.602 <0.001 汉族 368 39.05(31.23, 47.50) 398 35.60(30.73, 39.20) 脂肪体重(kg) 藏族 308 5.90(4.63, 7.60) 9.784 <0.001 364 9.65(6.88, 13.20) 11.160 <0.001 汉族 368 3.40(1.70, 6.10) 398 7.25(4.60, 10.30) 脂肪百分比(%) 藏族 308 14.89(11.28, 19.35) 10.397 <0.001 364 23.26(20.00, 26.76) 12.884 <0.001 汉族 368 8.27(3.68, 14.60) 398 16.84(12.68, 21.89) BMI:体重指数;FFMI:去脂体重指数;FMI:脂肪体重指数 比较同性别同年龄藏族和汉族青少年脂肪百分比的差异,结果显示从10岁到17岁各年龄组的藏族和汉族青少年脂肪百分比的差异均有统计学意义(P均<0.001)。随着年龄的变化,藏族和汉族青少年男性的脂肪百分比均呈逐渐下降趋势,而藏族和汉族青少年女性的脂肪百分比均呈逐渐上升趋势,但两民族间青少年脂肪百分比的差异始终存在,藏族青少年的脂肪百分比始终比同性别同年龄组的汉族青少年高4%~7%(表 2)。

表 2 各年龄段藏族和汉族青少年脂肪百分比比较年龄(岁) 民族 男性 女性 n (x±s)/M(Q1,Q3) Z值 P值 n (x±s)/M(Q1,Q3) Z值 P值 10 藏族 24 17.9(14.7, 20.4) 2.108 <0.001 39 20.3(16.7, 22.8) 5.271 <0.001 汉族 48 13.8(7.9, 19.7) 63 12.7(10.7, 16.3) 11 藏族 30 18.8(16.4, 21.2) 3.940 <0.001 51 20.1(17.5, 23.0) 5.451 <0.001 汉族 49 12.9(8.0, 17.5) 39 13.5(10.6, 16.3) 12 藏族 49 16.8(14.4, 20.7) 3.969 <0.001 55 20.1(16.6, 22.7) 3.771 <0.001 汉族 39 10.1(4.8, 16.4) 42 14.7(10.1, 18.6) 13 藏族 42 14.8(12.9, 19.9) 4.099 <0.001 68 22.7(20.3, 26.1) 6.668 <0.001 汉族 56 9.4(3.9, 15.0) 47 14.0(10.3, 19.2) 14 藏族 47 16.1(10.7, 20.2) 4.879 <0.001 64 25.7(21.0, 29.4) 4.725 <0.001 汉族 65 7.3(3.1, 12.4) 42 19.5(15.1, 23.4) 15 藏族 44 13.1(10.1, 16.3) 3.977 <0.001 53 26.2(22.6, 29.2) 3.601 <0.001 汉族 32 5.5(3.0, 12.3) 31 21.9(19.4, 21.6) 16 藏族 32 11.8(9.0, 16.7) 5.470 <0.001 35 25.6(23.6, 28.5) 5.616 <0.001 汉族 38 3.2(3.0, 8.1) 55 20.8(16.8, 23.2) 17 藏族 40 11.4(7.8, 14.1) 4.161 <0.001 33 26.8(24.6, 29.6) 5.952 <0.001 汉族 41 5.2(3.0, 8.6) 45 20.2(16.5, 22.9) 讨论

儿童青少年生长发育过程中,体内的脂肪体重、瘦体重、脂肪百分比等身体成分指标都在发生着变化[6],青春期前后是身体成分迅速发展和变化的重要时期。肥胖儿童和体重正常儿童身体成分比较研究表明,肥胖儿童的脂肪体重和瘦体重都比体重正常儿童要高[7]。因此,研究身体成分,特别是脂肪体重、瘦体重及脂肪百分比等指标对青少年发育状况研究意义重大。与平原地区相比,高原地区空气氧分压偏低,缺氧导致血液中血细胞和血红蛋白等增加,进而影响整个人体脏器,此外缺氧可以使细胞内许多因子发生代偿性变化,从而对缺氧作出应激反应。曾有研究发现藏族学生的抑郁、不受欢迎、躯体诉述、自伤、思维障碍、违纪和攻击等行为问题因子得分高于汉族学生,而且可能和生物学问题有关[8]。

本研究是首次通过大规模调查对居住在高海拔地区的藏族青少年和生活在低海拔地区的汉族青少年的身体成分进行比较的研究,研究样本具有较好的代表性和可靠性,有利于不同民族青少年的身体发育研究。本研究中两个民族青少年的体重差异无统计学意义,BMI差异不大,但藏族青少年的脂肪体重、脂肪百分比、FMI等指标都显著高于汉族,而其瘦体重、代谢率和去脂体重百分比都显著低于汉族青少年,男女都有相同的趋势。此外,在所有身体成分指标中,脂肪百分比是最具临床意义的一个指标,其变化可导致其他身体成分指标发生相应的变化。考虑到年龄对于脂肪百分比可能带来的影响,本研究在每一个年龄组分别比较同性别藏族和汉族青少年脂肪百分比的差异,结果发现每个年龄组的藏族青少年的脂肪百分比都比同性别的汉族青少年要高。有研究提示,世居高海拔地区的藏族人群对高原环境的适应机制不同于其他民族,经过数千年的漫长进化过程,对高原低氧环境的适应能力已达到更高的境界[9-12]。而且藏族人群的饮食习惯与汉族差异较大,藏族人群饮食结构单纯,食用乳制品、肉类、腌制食品、烟熏食品等比例较大,而较少食用新鲜蔬菜,可能这也是藏族青少年脂肪百分比显著高于汉族青少年的一个原因。也有研究认为藏族青少年的饮食习惯和其较高的消化道疾病发病率等相关[13-15]。

总之,生长在高原地区的藏族青少年,由于遗传、海拔、生活环境等多种原因导致其身体成分状况和长期生活在平原地区的汉族青少年不尽一致。藏族青少年的脂肪百分比始终高于同性别同年龄的汉族青少年。本研究对于了解各民族青少年的身体成分状况和身体发育情况具有重要意义。

作者贡献:陈博负责收集文献、撰写并修订文章; 阳惠湘负责提出选题思路,修订文章。利益冲突 无 -

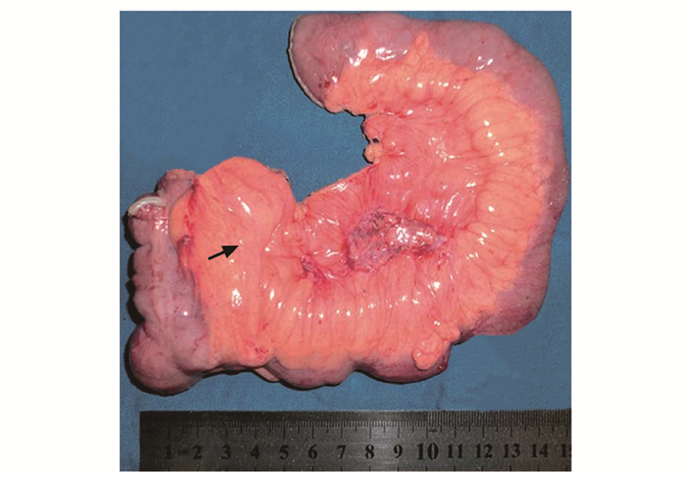

图 1 克罗恩病患者的病变肠切除标本[5]显示,增生的肠系膜脂肪组织(箭头)包绕肠管且超过其周长的50%,即“爬行脂肪征”

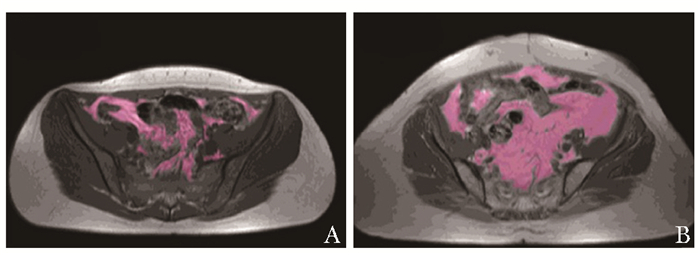

图 2 内脏脂肪组织(紫色)的MRI定量分析影像[6]

A.正常人; B.克罗恩病患者

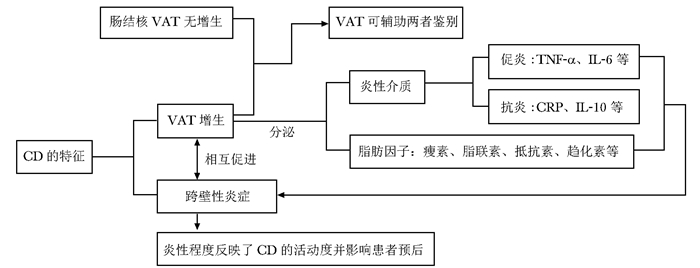

图 3 内脏脂肪组织与克罗恩病发病机制、病程及诊断的关系

VAT:内脏脂肪组织; CRP:C反应蛋白; CD、TNF-α、IL:同表 1

表 1 与CD相关的主要脂肪因子及功能

脂肪因子 功能 瘦素 促进TNF-α的产生,与TNF-α协同发挥促炎作用[13]; 调节辅助T细胞极化,通过记忆T细胞促进幼稚T细胞增殖和干扰素-γ的产生[14] 脂联素 具有不同的亚型,表现出不同的生物学效应[15] 抵抗素 由促炎细胞因子(IL-1、IL-6和TNF-α)诱导表达[16]; 通过NF-κB信号通路促进单核细胞表达TNF-α、IL-6和IL-12,发挥促炎活性[17] 趋化素 通过招募和激活抗原呈递细胞在炎症早期发挥作用,连接先天免疫和获得性免疫[18]; 是促进CD炎症反应的重要因子 CD:克罗恩病; TNF-α:肿瘤坏死因子-α; IL:白细胞介素; NF-κB:核因子-κB -

[1] Ramos GP, Papadakis KA. Mechanisms of Disease: Inflammatory Bowel Diseases[J]. Mayo Clin Proc, 2019, 94: 155-165. DOI: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.09.013

[2] Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD. Landmark article Oct 15, 1932. Regional ileitis. A pathological and clinical entity. By Burril B. Crohn, Leon Ginzburg, and Gordon D. Oppenheimer[J]. JAMA, 1984, 251: 73-79. DOI: 10.1001/jama.1984.03340250053024

[3] Chait A, den Hartigh LJ.Adipose Tissue Distribution, Inflammation and Its Metabolic Consequences, Including Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease[J]. Front Cardiovasc Med, 2020, 7: 22.

[4] Weakley FL, Turnbull RB. Recognition of regional ileitis in the operating room[J]. Dis Colon Rectum, 1971, 14: 17-23. DOI: 10.1007/BF02553169

[5] Li Y, Zhu WM, Zuo LG, et al. The Role of the Mesentery in Crohn's Disease: The Contributions of Nerves, Vessels, Lymphatics, and Fat to the Pathogenesis and Disease Course[J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2016, 22: 1483-1495. DOI: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000791

[6] Büning C, von Kraft C, Hermsdorf M, et al. Visceral Adipose Tissue in Patients with Crohn's Disease Correlates with Disease Activity, Inflammatory Markers, and Outcome[J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2015, 21: 2590-2597. DOI: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000527

[7] Sheehan AL, Warren BF, Gear MW, et al. Fat-wrapping in Crohn's disease: pathological basis and relevance to surgical practice[J]. Br J Surg, 1992, 79: 955-958. DOI: 10.1002/bjs.1800790934

[8] Yamamoto K, Kiyohara T, Murayama Y, et al. Production of adiponectin, an anti-inflammatory protein, in mesenteric adipose tissue in Crohn's disease[J]. Gut, 2005, 54: 789-796. DOI: 10.1136/gut.2004.046516

[9] Peyrin-Biroulet L, Chamaillard M, Gonzalez F, et al. Mesenteric fat in Crohn's disease: a pathogenetic hallmark or an innocent bystander?[J]. Gut, 2007, 56: 577-583. DOI: 10.1136/gut.2005.082925

[10] Moran GW, Dubeau MF, Kaplan GG, et al.The Increasing Weight of Crohn's Disease Subjects in Clinical Trials: A Hypothesis-generatings Time-trend Analysis[J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2013, 19: 2949-2956. DOI: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e31829936a4

[11] Peyrin-Biroulet L, Gonzalez F, Dubuquoy L, et al. Mesenteric fat as a source of C reactive protein and as a target for bacterial translocation in Crohn's disease[J]. Gut, 2012, 61: 78-85. DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300370

[12] Fink C, Karagiannides I, Bakirtzi K, et al. Adipose tissue and inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis[J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2012, 18: 1550-1557. DOI: 10.1002/ibd.22893

[13] Raso GM, Pacilio M, Esposito E, et al. Leptin potentiates IFN-gamma-induced expression of nitric oxide synthase and cyclo-oxygenase-2 in murine macrophage J774A.1[J]. Br J Pharmacol, 2002, 137: 799-804. DOI: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704903

[14] Arvind B, Besir O, Rainer G, et al. Leptin: a critical regulator of CD4+T-cell polarization in vitro and in vivo[J]. Endocrinology, 2010, 151: 56-62. DOI: 10.1210/en.2009-0565

[15] Schäffler A, Schölmerich J. The role of adiponectin in inflammatory gastrointestinal diseases[J]. Gut, 2009, 58: 317-322. DOI: 10.1136/gut.2008.159210

[16] Park HK, Kwak MK, Kim HJ, et al. Linking resistin, inflammation, and cardiometabolic diseases[J]. Korean J Intern Med, 2017, 32: 239-247. DOI: 10.3904/kjim.2016.229

[17] Bokarewa M, Nagaev I, Dahlberg L, et al. Resistin, an adipokine with potent proinflammatory properties[J]. J Immunol, 2005, 174: 5789-5795. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5789

[18] Mariani F, Roncucci L. Chemerin/chemR23 axis in inflammation onset and resolution[J]. Inflamm Res, 2015, 64: 85-95. DOI: 10.1007/s00011-014-0792-7

[19] Carrión M, Frommer KW, Pérez-García S, et al. The Adipokine Network in Rheumatic Joint Diseases[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2019, 20: 4091. DOI: 10.3390/ijms20174091

[20] Drouet M, Dubuquoy L, Desreumaux P, et al. Visceral fat and gut inflammation[J]. Nutrition, 2012, 28: 113-117. DOI: 10.1016/j.nut.2011.09.009

[21] Barbier M, Vidal H, Desreumaux P, et al. Overexpression of leptin mRNA in mesenteric adipose tissue in inflammatory bowel diseases[J]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol, 2003, 27: 987-991.

[22] Erhayiem B, Dhingsa R, Hawkey CJ, et al. Ratio of Visceral to Subcutaneous Fat Area Is a Biomarker of Complicated Crohn's Disease[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2011, 9: 684-687. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.05.005

[23] Konstantinos K, Koutroubakis IE, Costas X, et al. Circulating levels of leptin, adiponectin, resistin, and ghrelin in inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2006, 12: 100-105. DOI: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000200345.38837.46

[24] Rodrigues VS, Milanski M, Fagundes JJ, et al. Serum levels and mesenteric fat tissue expression of adiponectin and leptin in patients with Crohn's disease[J]. Clin Exp Immunol, 2012, 170: 358-364. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2012.04660.x

[25] Zielińska A, Siwiński P, Sobolewska-Włodarczyk A, et al. The role of adipose tissue in the pathogenesis of Crohn's disease[J]. Pharmacol Rep, 2019, 71: 105-111. DOI: 10.1016/j.pharep.2018.09.011

[26] Peng YJ, Shen TL, Chen YS, et al. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptor 1 overexpression enhance inflammatory bowel disease[J]. J Biomed Sci, 2018, 25: 24. DOI: 10.1186/s12929-018-0419-3

[27] Pajvani UB, Hawkins M, Combs TP, et al. Complex Distribution, Not Absolute Amount of Adiponectin, Correlates with Thiazolidinedione-mediated Improvement in Insulin Sensitivity[J]. J Biol Chem, 2004, 279: 12152-12162. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M311113200

[28] Boström EA, Ekstedt M, Kechagias S, et al. Resistin is associated with breach of tolerance and anti-nuclear antibodies in patients with hepatobiliary inflammation[J]. Scand J Immunol, 2011, 74: 463-470. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2011.02592.x

[29] Konrad A, Lehrke M, Schachinger V, et al. Resistin is an inflammatory marker of inflammatory bowel disease in humans[J]. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2007, 19: 1070-1074. DOI: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f16251

[30] Weigert J, Obermeier F, Neumeier M, et al. Circulating levels of chemerin and adiponectin are higher in ulcerative colitis and chemerin is elevated in Crohn's disease[J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2010, 16: 630-637. DOI: 10.1002/ibd.21091

[31] Terzoudis S, Malliaraki N, Damilakis J, et al. Chemerin, visfatin, and vaspin serum levels in relation to bone mineral density in patients with inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2016, 28: 814-819. DOI: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000617

[32] Romacho T, Valencia I, Ramos-González M, et al. Visfatin/ eNampt induces endothelial dysfunction in vivo: a role for Toll-Like Receptor 4 and NLRP3 inflammasome[J]. Sci Rep, 2020, 10: 5386. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-62190-w

[33] Tiaka EK, Manolakis AC, Kapsoritakis AN, et al. Unravel-ing the link between leptin, ghrelin and different types of colitis[J]. Ann Gastroenterol, 2011, 24: 20-28.

[34] Roma E, Krini M, Hantzi E, et al. Retinol Binding Protein 4 in children with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: a negative correlation with the disease activity[J]. Hippokratia, 2012, 16: 360-365.

[35] Reinehr T, Roth CL. Inflammation Markers in Type 2 Diabetes and the Metabolic Syndrome in the Pediatric Population[J]. Curr Diab Rep, 2018, 18: 131. DOI: 10.1007/s11892-018-1110-5

[36] Borley NR, Mortensen NJ, Jewell DP, et al. The relation-ship between inflammatory and serosal connective tissue changes in ileal Crohn's disease: evidence for a possible causative link[J]. J Pathol, 2000, 190: 196-202. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200002)190:2<196::AID-PATH513>3.0.CO;2-5

[37] Li Y, Zhu WM, Gong JF, et al. Influence of exclusive enteral nutrition therapy on visceral fat in patients with Crohn's disease[J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2014, 20: 1568-1574. DOI: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000114

[38] Van Der Sloot KW, Joshi AD, Bellavance DR, et al. Visceral Adiposity, Genetic Susceptibility, and Risk of Complications Among Individuals with Crohn's Disease[J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2017, 23: 82-88. DOI: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000978

[39] Uko V, Vortia E, Achkar JP, et al. Impact of abdominal visceral adipose tissue on disease outcome in pediatric Crohn's disease[J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2014, 20: 2286-2291. DOI: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000200

[40] Cravo ML, Velho S, Torres J, et al. Lower skeletal muscle attenuation and high visceral fat index are associated with complicated disease in patients with Crohn's disease: An exploratory study[J]. Clin Nutr ESPEN, 2017, 21: 79-85. DOI: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2017.04.005

[41] Holt DQ, Moore GT, Strauss BJ, et al. Visceral adiposity predicts post-operative Crohn's disease recurrence[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2017, 45: 1255-1264. DOI: 10.1111/apt.14018

[42] Ding Z, Wu XR, Remer EM, et al. Association between high visceral fat area and postoperative complications in patients with Crohn's disease following primary surgery[J]. Colorectal Dis, 2016, 18: 163-172. DOI: 10.1111/codi.13128

[43] Maconi G, Greco S, Duca P, et al. Prevalence and clinical significance of sonographic evidence of mesenteric fat alterations in Crohn's disease[J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2008, 14: 1555-1561. DOI: 10.1002/ibd.20515

[44] 中华医学会消化病学分会炎症性肠病学组.炎症性肠病诊断与治疗的共识意见(2018年, 北京)[J].中华消化杂志, 2018, 38: 292-311. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Group, Chinese Society of Gastroenterology, Chinese Medical Association. Chinese con-sensus on diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease(Beijing, 2018)[J]. Zhonghua Xiao Hua Za Zhi, 2018, 38: 292-311.

[45] Yadav DP, Madhusudhan KS, Kedia S, et al. Development and validation of visceral fat quantification as a surrogate marker for differentiation of Crohn's disease and intestinal tuberculosis[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2017, 32: 420-426. DOI: 10.1111/jgh.13535

[46] Ko JK, Lee HL, Kim JO, et al. Visceral fat as a useful parameter in the differential diagnosis of Crohn's disease and intestinal tuberculosis[J]. Intest Res, 2014, 12: 42-47. DOI: 10.5217/ir.2014.12.1.42

[47] Osterman MT, Kundu R, Lichtenstein GR, et al. Associa-tion of 6-thioguanine nucleotide levels and inflammatory bowel disease activity: a meta-analysis[J]. Gastroenterology, 2006, 130: 1047-1053. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.046

[48] Holt DQ, Strauss BJ, Moore GT. Weight and Body Composition Compartments do Not Predict Therapeutic Thiopurine Metabolite Levels in Inflammatory Bowel Disease[J]. Clin Transl Gastroenterol, 2016, 7: e199. DOI: 10.1038/ctg.2016.56

[49] Shen WS, Cao L, Li Y, et al. Visceral Fat Is Associated With Mucosal Healing of Infliximab Treatment in Crohn's Disease[J]. Dis Colon Rectum, 2018, 61: 706-712. DOI: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001074

-

期刊类型引用(5)

1. 高新颖,宇克莉,张兴华,姚玥彤,肖瑶,程智,高雯芳,刘鑫,包金萍. 云南佤族三大方言族群的体成分. 人类学学报. 2024(03): 458-469 .  百度学术

百度学术

2. 于季红,王山,倪文凤,董博,吴立本,康霞,田芬芬,桑培培,程昱璇,吴珏,石金龙,田亚平,何昆仑,王艳. 驻高原官兵体形态成分及血清生化指标与体能素质相关性研究. 解放军医学院学报. 2022(12): 1277-1282+1287 .  百度学术

百度学术

3. 陈婷,申艳,史展雨,王叶秋,赵昕. 藏汉大学生身体机能差异研究. 高原科学研究. 2021(04): 59-66 .  百度学术

百度学术

4. 敬剑英,王东生,周林勇,李建水,谷君卿,庞飞,达娃恩珠,谢亮. 藏族泡型肝棘球蚴病患者的术前营养状况及其与一般情况和临床指标的相关性. 广西医学. 2020(15): 2040-2043+2046 .  百度学术

百度学术

5. 曾强. 河南驻马店市中小学学生体成分分析. 现代预防医学. 2018(17): 3122-3124+3129 .  百度学术

百度学术

其他类型引用(1)

作者投稿

作者投稿 专家审稿

专家审稿 编辑办公

编辑办公 邮件订阅

邮件订阅 RSS

RSS

下载:

下载: