Serum Uric Acid Levels in Chinese Patients with Classic Multiple Sclerosis: Before and After Treatment with Interferon-beta 1b

-

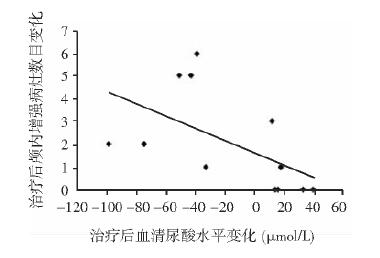

摘要:目的 探讨中国经典型多发性硬化(classical multiple sclerosis, CMS)患者β干扰素-1b治疗前后血清尿酸(uric acid, UA)水平的变化及其与复发率、扩展残疾状态评分(Expanded Disability Status Scale, EDSS)和颅内增强病灶(contrast-enhancing lesions, CELs)数目间的关系。方法 12例CMS患者(10例女性, 2例男性, 年龄:24~54岁)被纳入至一项为期6个月的疗效观察研究。在疾病缓解期, 给予β干扰素-1b(250 μg, 皮下注射, 隔日1次)治疗。治疗前后评估患者EDSS评分、年复发次数、颅内CELs数目和血清UA水平。结果 治疗后, 患者年复发次数(0.0比0.9, P=0.011)和颅内CELs数目(0.0比1.5, P=0.007)较治疗前明显减低; EDSS评分有降低趋势(2.0比2.8), 但差异无统计学意义(P=0.064);血清UA水平从222.2 μmol/L升高至234.9 μmol/L, 但差异亦无统计学意义(P=0.213)。进一步研究发现, 血清UA水平升高与颅内CELs数目减低显著相关(r=-0.716, P=0.009)。结论 血清UA水平有可能成为评估CMS患者对β干扰素-1b治疗反应的一个监测指标。Abstract:Objective To investigate the changes of serum uric acid (UA) level and its relationship with relapse rate, Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score, and the number of contrast-enhancing lesions (CELs) in Chinese patients with classic multiple sclerosis (CMS) before and after interferon (IFN) -beta 1b treatment.Methods Twelve patients (10 women and 2 men, aged 24 to 54 years) with definite CMS were enrolled into a 6-month open-label observational treatment study. IFN-beta 1b (250 μg, qod) was injected subcutaneously during remission stage. EDSS, relapse rate, number of CELs, and serum UA levels were examined both at baseline and at the end of the study.Results After treatment, the median relapse rate (0.0 vs. 0.9, P=0.011) and median number of CELs (0.0 vs. 1.5, P=0.007) decreased significantly compared with those before treatment. The median EDSS score also decreased from 2.8 to 2.0, but the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.064). Serum UA level increased from 222.2 μmol/L to 239.4 μmol/L after treatment, although the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.213). However, there was significant correlation between the increase in UA level and the decrease in number of CELs (r=-0.716, P=0.009).Conclusions UA may serve as an easily detectable and economic marker for the blood-brain barrier function in CMS patients and for the responses to IFN-beta 1b treatment.

-

Keywords:

- multiple sclerosis /

- uric acid /

- interferon-beta

-

多发性硬化(multiple sclerosis,MS)是中枢神经系统炎性脱髓鞘性疾病,一氧化氮(nitric oxide,NO)及其氧化物———过氧亚硝酸(peroxynitrite,PN)在其发生发展中具有重要作用[1-3]。尿酸(uric acid,UA)因其可抑制PN而被认为对MS具有一定保护作用[4]。动物研究显示UA具有治疗效应[5-6]; 临床研究发现高尿酸血症患者很少患MS[6],而MS患者血清UA水平明显低于健康人[6-11]。但是,这一结论仍有争议[12-17],而且血清UA水平可能随疾病所处阶段不同而有不同变化[9]。有学者指出UA可能具有双重作用:神经保护作用和破坏作用[12]。

目前,疾病调节治疗(disease-modifying therapy,DMT)是MS的一线治疗方法,药物包括β干扰素-1b、β干扰素-1a和醋酸格列默。有研究显示DMT可影响MS患者血清UA水平,但结论不一[11, 17-19]。有关β干扰素-1b对血清UA水平作用的研究至今鲜有报道。

本开放性前瞻性疗效观察研究旨在探讨β干扰素-1b对中国经典型MS (classical MS,CMS)患者血清UA水平的影响及血清UA水平与患者残疾程度、复发情况和颅内磁共振(magnetic resonance imaging,MRI)病灶数目间的关系。

对象和方法

对象

本研究共纳入2007年1月至2008年12月在北京协和医院神经科就诊并接受β干扰素-1b治疗的确诊CMS患者12例,其中女10例,男2例。CMS诊断依据2005年McDonald标准[20]。所有患者入组前未接受过DMT或免疫抑制剂治疗; 均处于缓解期,且至少3个月内未接受过激素治疗; 无肾脏疾病、痛风或糖尿病。12例患者中,复发缓解型10例,继发进展型2例。所有患者治疗前后均进行扩展残疾状态评分(Expanded Disability Status Scale,EDSS)。

β干扰素-1b治疗

β干扰素-1b (倍泰龙,中国北京拜耳先灵公司)的使用方法为将其溶解于0. 54%的盐水中,250 μg皮下注射,隔日1次。在接受β干扰素-1b治疗的6个月期间,所有患者无任何饮食习惯改变,且未服用任何影响UA水平的药物。

MRI检查

MRI检查在1. 5T MRI机器上(GE,Sigma,Milwaukii,USA)进行,增强扫描采用国际标准程序,在注射0. 1 mmol/kg钆喷酸葡胺后5 min进行扫描。收集颅内增强病灶(contrast-enhancing lesions,CELs)数目。

血清UA水平检测

行MRI检查当天,完成血液标本采集。患者隔夜空腹,从肘静脉采集血液标本。血清UA水平用试剂盒(Olympus Diagnostica GmbH,Hamburg,Germany)检测,方法为酶学法,步骤严格参照说明书进行。实验室血清UA正常值女性为140 ~390 μmol/L,男性为200 ~ 500 μmol/L。

统计学处理

所有统计分析均采用SPSS统计学软件(version 11. 0,Chicago,IL,USA)完成。结果用x ± s或中位数表示。配对t检验用于比较治疗前后的数据变化。变量间的相关性则用Spearman线性回归进行分析。以P<0. 05为差异有统计学意义。

结 果

基线临床资料

12例患者的平均年龄为(33. 4 ± 8. 0)岁(24 ~ 54岁),平均发病年龄为(27. 4 ± 9. 8)岁(7. 8 ~ 46. 0岁); 治疗开始前患者病程中位数为2. 3年(1. 0 ~ 28. 3年),中位复发次数为2次(1 ~ 8次),入组前1年内中位复发次数为1次(1 ~ 2次)。

β干扰素-1b可减少患者年复发次数和颅内CELs数目,但不能降低EDSS评分

本研究无患者脱落。与治疗前相比,治疗后的年复发次数和CELs数目均显著降低(P<0. 05); EDSS评分有降低趋势,但差异无统计学意义(P = 0. 064) (表 1)。

表 1 β干扰素-1b对患者EDSS、年复发次数、颅内增强病灶数目及血清尿酸水平的影响时间 EDSS (中位数) 年复发次数(中位数) 颅内增强病灶数目(中位数) 尿酸(μmol/L,x ± s) 治疗前(缓解期) 2.8 0.9 1.5 222. 2 ± 28. 9 治疗后6个月 2.0 0.0 0.0 239. 4 ± 48. 7 P值 0.064 0.011 0.007 0.213 EDSS:扩展残疾状态评分 药物不良反应

用药期间,6例(50%)患者出现流感样症状,4例(31%)患者出现注射局部反应,2例(17%)患者甲状腺激素刺激素降低,1例(8%)患者谷丙氨酸转移酶升高。所有上述不良反应均为轻到中度,且为一过性。

血清UA水平

治疗前,仅1例男性患者血清UA水平(186 μmol/L)低于正常。治疗后,所有患者血清UA水平均在正常范围内,平均血清UA水平由(222. 2 ± 28. 9) μmol/L升高至(239. 4 ± 48. 7) μmol/L,但差异未达到统计学意义(P = 0. 213) (表 1)。进一步相关性分析显示,治疗后血清UA浓度变化与CELs数目变化呈显著负相关(r =- 0. 716,P = 0. 009) (图 1)。

讨 论

本研究显示,经6个月β干扰素-1b治疗后,CMS患者年复发次数与CELs数目显著降低,提示β干扰素-1b对中国初治CMS患者,在临床复发性和MRI活动性方面的疗效与白种人相当[21-26]。至今,有关β干扰素1b对EDSS评分影响的报道尚存争议,一些研究显示长期β干扰素1b治疗可改善MS患者EDSS评分[21-23],而其他一些研究未能证明这一获益[27-31]。本研究观察到CMS患者EDSS评分在6个月治疗后有改善趋势,但差异未达到统计学意义,可能与本研究随访时期较短有关。

值得一提的是,本研究观察到CMS患者经β干扰素-1b治疗后血清UA水平有升高趋势,且血清UA水平的升高与治疗后患者CELs数目的降低显著相关,笔者推测这可能与血脑屏障破坏的减少有关。血脑屏障破坏是MS的特点之一,通常用CELs来评估[32]。在健康人中,UA并不穿过血脑屏障,血清中UA水平至少比脑脊液中高10倍[7]; 在血脑屏障破坏的MS患者,血清UA水平较血脑屏障正常者显著降低[9]; 在MS动物模型中,血脑屏障破坏可以导致脑脊液UA水平升高[5]; 这些均提示血清UA水平高低与血脑屏障破坏程度相关,本研究中发现的血清UA水平升高和血脑屏障破坏减少之间的相关性与上述研究结果一致。因此,笔者推测,相比价格昂贵的MRI检查,血清UA水平的变化也许可以成为评价MS患者血脑屏障功能更经济的指标。

已有研究证实,MS患者血脑屏障破坏与内皮细胞功能障碍有关。正常情况下,脑内皮细胞的紧密连接可限制激活的白细胞穿过血脑屏障进入脑组织。在MS的病理状态下,前炎症细胞因子通过上调黏附分子、破坏紧密连接的完整性和释放内皮微粒导致血脑屏障破坏[33]。有研究证实β干扰素-1b可改善内皮功能,从而抑制血脑屏障开放。这些机制包括抑制紧密连接完整性的破坏[34],抑制内皮细胞表达黏附分子等[35-37]。由此,笔者推测β干扰素-1b对血脑屏障开放的抑制作用可能是其导致MS患者血清UA水平有升高趋势的机制之一。尽管这一结果没有达到统计学意义,这可能与本研究患者病例数较少有关。因此,为进一步验证β干扰素-1b对血清UA水平的影响,还需进行大规模的研究。

本研究尚存一些不足之处,如:样本量较小,为开放性研究,缺乏安慰剂对照等。因此,为了证实上述结果,以及证实UA能否作为评估血脑屏障功能和评价患者对β干扰素-1b反应性的更简单、经济的指标,还需进行更大规模的双盲安慰剂对照研究。

-

表 1 β干扰素-1b对患者EDSS、年复发次数、颅内增强病灶数目及血清尿酸水平的影响

时间 EDSS (中位数) 年复发次数(中位数) 颅内增强病灶数目(中位数) 尿酸(μmol/L,x ± s) 治疗前(缓解期) 2.8 0.9 1.5 222. 2 ± 28. 9 治疗后6个月 2.0 0.0 0.0 239. 4 ± 48. 7 P值 0.064 0.011 0.007 0.213 EDSS:扩展残疾状态评分 -

[1] Liu JS, Zhao ML, Brosnan CF, et al. Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and nitrotyrosine in multiple sclerosis lesions[J]. Am J Pathol, 2001, 158:2057-2066. DOI: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64677-9

[2] Tran EH, Hardin-Pouzet H, Verge G, et al. Astrocytes and microglia express inducible nitric oxide synthase in mice with experimental allergic encephalomyelitis[J]. J Neuroimmunol, 1997, 74:121-129. DOI: 10.1016/S0165-5728(96)00215-9

[3] Mitrovic B, Ignarro LJ, Montestruques S, et al. Nitric oxide as a potential pathological mechanism in demyelination:its differential effects on primary glial cells in vitro[J]. Neuroscience, 1994, 61:575-585. DOI: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90435-9

[4] Squadrito GL, Cueto R, Splenser AE, et al. Reaction of uric acid with peroxynitrite and implications for the mechanism of neuroprotection by uric acid[J]. Arch Biochem Biophys, 2000, 376:333-337. DOI: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1721

[5] Scott GS, Spitsin SV, Kean RB, et al. Therapeutic intervention in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by administration of uric acid precursors[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2002, 99:16303-16308. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.212645999

[6] Hooper DC, Spitsin K, Kean RB, et al. Uric acid, a natural scavenger of peroxynitrite, in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1998, 95:675-680. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.95.2.675

[7] Zamani A, Rezaei A, Khaeir F, et al. Serum and cerebrospinal fluid uric acid levels in multiple sclerosis patients[J]. Clin Neurol Neurosurg, 2008, 110:642-643. DOI: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2008.03.002

[8] Sotgiu S, Pugliatti M, Sanna A, et al. Serum uric acid and multiple sclerosis[J]. Neurol Sci, 2002, 23:183-188. DOI: 10.1007/s100720200059

[9] Rentzos M, Nikolaou C, Anagnostouli M, et al. Serum uric acid and multiple sclerosis[J]. Clin Neurol Neurosurg, 2006, 108:527-531. DOI: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2005.08.004

[10] Spitsin S, Hooper DC, Mikheeva T, et al. Uric acid levels in patients with multiple sclerosis:analysis in mono- and dizygotic twins[J]. Mult Scler, 2001, 7:165-166. DOI: 10.1177/135245850100700305

[11] Toncev G, Milicic B, Toncev S, et al. Serum uric acid levels in multiple sclerosis patients correlate with activity of disease and blood-brain barrier dysfunction[J]. Eur J Neurol, 2002, 9:221-226. DOI: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2002.00384.x

[12] Mostert JP, Ramsaransing SM, Heersema DJ, et al. Serum acid levels and leukocyte nitric oxide production in multiple sclerosis patients outside relapses[J]. J Neurol Sci, 2005, 231:41-44. DOI: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.12.008

[13] Kastenbauer S, Kieseier BC, Becker BF. No evidence of increased oxidative degradation of urate to allantoin in the CSF and serum of patients with multiple sclerosis[J]. J Neurol, 2005, 252:611-612. DOI: 10.1007/s00415-005-0697-z

[14] Ramsaransing GSM, Heersema DJ, De Keyser J. Serum uric acid, dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate, and apolipoprotein E genotype in benign vs. progressive multiple sclerosis[J]. Eur J Neurol, 2005, 12:514-518. DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2005.01009.x

[15] Drulovic J, Dujmovic I, Stojsavljevic N, et al. Uric acid levels in sera from patients with multiple sclerosis[J]. J Neurol, 2001, 248:121-126. DOI: 10.1007/s004150170246

[16] Karg E, Klivenyi P, Nemeth I, et al. Nonenzymatic antioxidants of blood in multiple sclerosis[J]. J Neurol, 1999, 246:533-539. DOI: 10.1007/s004150050399

[17] Peng F, Zhang B, Zhong X, et al. Serum uric acid levels of patients with multiple sclerosis and other neurological diseases[J]. Mult Scler, 2008, 14:188-196. DOI: 10.1177/1352458507082143

[18] Constantinescu C, Freitag P, Kappos L. Increase in serum levels of uric acid, endogenous antioxidant, under treatment with glatiramer acetate for multiple sclerosis[J]. Mult Scler, 2000, 6:378-381. DOI: 10.1177/135245850000600603

[19] Guerrero AL, Martín-Polo J, Laherrán E, et al. Variation of serum uric acid levels in multiple sclerosis during relapses and immunomodulatory treatment[J]. Eur J Neurol, 2008, 15:394-397. DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02087.x

[20] Polman CH, Reingold SC, Edan G, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis:2005 revisions to the "McDonald Criteria"[J]. Ann Neurol, 2005, 58:840-846. DOI: 10.1002/ana.20703

[21] Lövblad KO, Anzalone N, Dörfler A, et al. MR imaging in multiple sclerosis:review and recommendations for current practice[J]. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2010, 31:983-989. DOI: 10.3174/ajnr.A1906

[22] Mowry EM, Beheshtian A, Waubant E, et al. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis is associated with lesion burden and brain volume measures[J]. Neurology, 2009, 72:1760-1785. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a609f8

[23] Brex PA, Molyneux PD, Smiddy P, et al. The effect of IFN beta-1b on the evolution of enhancing lesions in secondary progressive MS[J]. Neurology, 2001, 57:2185-2190. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.57.12.2185

[24] Milanese C, Mantia LL, Palumbo R, et al. A post-marketing study on interferon-beta 1b and 1a treatment in relapsingremitting multiple sclerosis:different response in drop-outs and treated patients[J]. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 2003, 74:1689-1692. DOI: 10.1136/jnnp.74.12.1689

[25] Barkhof F, Polman CH, Radue EW, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging effects of interferon beta-1b in the BENEFIT study:integrated 2-year results[J]. Arch Neurol, 2007, 64:1292-1298. DOI: 10.1001/archneur.64.9.1292

[26] Gaindh D, Jeffries N, Ohayon J, et al. The effect of interferon beta-1b on size of short-lived enhancing lesions in patients with multiple sclerosis[J]. Expert Opin Biol Ther, 2008, 8:1823-1829. DOI: 10.1517/14712590802510629

[27] Khan OA, Tselis AC, Kamholz JA, et al. A prospective, open-label treatment trial to compare the effect of IFNβ-1a (Avonex), IFNβ-1b (Betaseron), and glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) on the relapse rate in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis[J]. Eur J Neurol, 2001, 8:141-148. DOI: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2001.00189.x

[28] Etemadifar M, Janghorbani M, Shaygannejad V. Comparison of Betaferon, Avonex, and Rebif in treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis[J]. Acta Neurol Scand, 2006, 113:283-287. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/16629762

[29] Flechter S, Vardi J, Finkelstein Y, et al. Cognitive dysfunction evaluation in multiple sclerosis patients treated with interferon beta-1b:an open-label prospective 1 year study[J]. Isr Med Assoc J, 2007, 9:457-459. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17642394

[30] Lily O, McFadden E, Hensor E, et al. Disease-specific quality of life in multiple sclerosis:the effect of disease modifying treatment[J]. Mult Scler, 2006, 12:808-813. DOI: 10.1177/1352458506070946

[31] Trojano M, Paolicelli D, Zimatore GB, et al. The IFNbeta treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS) in clinical practice:the experience at the MS Center of Bari, Italy[J]. Neurol Sci, 2005, 26:S179-S182. DOI: 10.1007/s10072-005-0511-9

[32] Trojano M, Liguori M, Paolicelli D, et al. Interferon beta in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis:an independent postmarketing study in southern Italy[J]. Mult Scler, 2003, 9:451-457. DOI: 10.1191/1352458503ms948oa

[33] Flechter S, Vardi J, Pollak L, et al. Comparison of glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) and interferon beta-1b (Betaferon) in multiple sclerosis patients:an open-label 2-year follow-up[J]. J Neurol Sci, 2002, 197:51-55. DOI: 10.1016/S0022-510X(02)00047-3

[34] Grossman RI, Braffman BH, Brorson JR, et al. Multiple sclerosis:serial study of gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging[J]. Radiology, 1988, 169:117-122. DOI: 10.1148/radiology.169.1.3420246

[35] Jimenez J, Jy W, Mauro LM, et al. Elevated endothelial microparticle-monocyte complexes induced by multiple sclerosis plasma and the inhibitory effects of interferon-beta 1b on release of endothelial microparticles, formation and transendothelial migration of monocyte-endothelial microparticle complexes[J]. Mult Scler, 2005, 11:310-315. DOI: 10.1191/1352458505ms1184oa

[36] Minagar A, Long A, Ma T, et al. Interferon (IFN) -beta 1a and IFN-beta 1b block IFN-gamma-induced disintegration of endothelial junction integrity and barrier[J]. Endothelium, 2003, 10:299-307. DOI: 10.1080/10623320390272299

[37] Trojano M, Defazio G, Avolio C, et al. Effects of rIFN-beta-1b on serum circulating ICAM-1 in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis and on the membrane-bound ICAM-1 expression on brain microvascular endothelial cells[J]. J Neurovirol, 2000, 6(Suppl 2):S47-S51. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10871785

-

期刊类型引用(2)

1. 隋莹莹,赵薇,王峥. 1例嗜铬细胞瘤伴儿茶酚胺心肌病患者围手术期的护理. 医药前沿. 2025(09): 107-110 .  百度学术

百度学术

2. 唐维晞,邓和平,陈彦汝,叶莎,张念. 心肌酶谱、动态心电图及冠状动脉CT血管造影诊断嗜铬细胞瘤儿茶酚胺性心脏损害价值研究. 现代生物医学进展. 2021(07): 1296-1300+1364 .  百度学术

百度学术

其他类型引用(0)

作者投稿

作者投稿 专家审稿

专家审稿 编辑办公

编辑办公 邮件订阅

邮件订阅 RSS

RSS

下载:

下载: