Association Between Coffee Consumption and Pain: A Cross-sectional Study Based on American National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

-

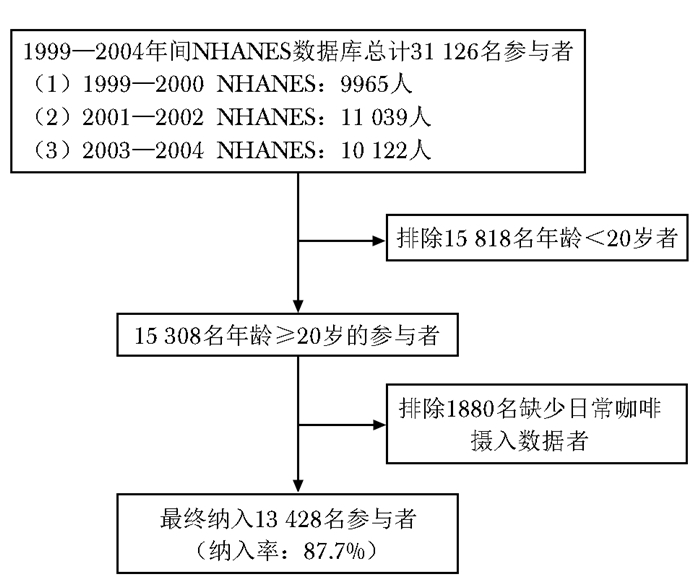

摘要:目的 基于公开数据库中的大样本信息,探究日常咖啡摄入与不同类型疼痛之间的相关性。方法 提取美国国家卫生和营养检查调查(National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey,NHANES)数据库中1999—2000年、2001—2002年、2003—2004年3个周期受试者的咖啡摄入、疼痛及11个协变量(包括年龄、性别、种族、受教育程度等)数据,采用无序多分类Logistic回归法构建3种模型评估日常咖啡摄入与疼痛之间的相关性。结果 共入选符合纳入与排除标准的受试者13 428名,其平均年龄为(49.79±19.06)岁,男女比例为0.9∶1。每日咖啡摄入情况:无咖啡摄入7794名(58.0%),>0~2杯咖啡摄入2077名(15.5%),>2杯咖啡摄入3557名(26.5%);每日咖啡因摄入情况:无咖啡因摄入7794名(58.0%),>0~200 mg咖啡因摄入3152名(23.5%),>200 mg咖啡因摄入2482名(18.5%)。疼痛情况:无疼痛或疼痛持续时间<24 h 10 202名(76.0%),急性疼痛910名(6.8%),亚急性疼痛369名(2.7%),慢性疼痛1947名(14.5%)。经权重估算,13 428名受试者预计可代表 1.9亿(190 709 157名)年龄≥20岁的美国公民,该期间美国人群急性疼痛、亚急性疼痛、慢性疼痛总体患病率分别为8%、3%、16%。Logistic回归分析显示,在未对任何协变量进行校正时,相较于每日无咖啡/咖啡因摄入者,每日咖啡摄入>2杯(OR=1.354, 95% CI:1.187~1.544)或咖啡因摄入>200 mg(OR=1.372, 95% CI:1.185~1.587)人群出现慢性疼痛的风险增加;当校正年龄、性别、种族的影响后,可得到相近结果,OR值分别为1.243(95% CI:1.083~1.427)和1.249(95% CI:1.072~1.456);当对11个协变量均进行校正时,未发现每日咖啡摄入杯数及咖啡因摄入量与慢性疼痛具有明显相关性。3种模型均未发现每日咖啡摄入杯数、咖啡因摄入量与急性疼痛、亚急性疼痛存在相关性。结论 与不摄入咖啡者相比,每日大量摄入咖啡者出现慢性疼痛的风险增高,但此种相关性受多种因素的影响;尚未发现日常咖啡摄入与急性疼痛、亚急性疼痛存在明显相关性。仍需开展基础研究和前瞻性临床试验进一步明确咖啡摄入与慢性疼痛之间的因果关系及其确切作用机制。Abstract:Objective To elucidate whether coffee consumption and caffeine intake was associated with various subtypes of pain based on extensive data from publicly accessible databases.Methods The information was extracted from three cycles of the American National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1999—2000, 2001—2002, 2003—2004), encompassing data on coffee consumption, pain information, and 11 covariates (including age, gender, race, etc.). Multinomial logistic regression in three models were utilized for analysis.Results A total of 13 428 participants were included in this study, with a mean age of (49.79±19.06)years and a male-to-female ratio of 0.9∶1. Daily coffee intake: non-drinker 7794(58.0%), > 0-2 cups 2077(15.5%), > 2 cups 3557(26.5%); daily caffeine intake: without intake 7794(58.0%), > 0-200 mg 3152(23.5%), > 200 mg 2482(18.5%); pain situation: no pain or pain duration < 24 h 10 202(76.0%), acute pain 910(6.8%), subacute pain 369(2.7%), chronic pain 1947(14.5%). After weighting, 13 428 participants were expected to represent 190 million(190 709 157) U.S. citizens aged ≥20 years, and the overall prevalence of acute, subacute, and chronic pain in the U.S. population during that period was estimated to be 8%, 3%, and 16%, respectively. Without adjusting for covariates, individuals who consumed more than 2 cups of coffee or 200 mg of caffeine per day exhibited an elevated risk of chronic pain compared to non-coffee/caffeine drinkers, with an odds ratio of 1.354(95% CI: 1.187-1.544) and 1.372(95% CI: 1.185-1.587), respectively. After adjusting for partial covariates including age, sex, and race, individuals who consumed more than 2 cups of coffee or more than 200 mg of caffeine per day still demonstrated an increased risk of chronic pain with an odds ratio of 1.243(95% CI: 1.083-1.427) and 1.249 (95% CI: 1.072-1.456), respectively. However, after all covariates were adjusted, there was no significant association between coffee/caffeine consumption and chronic pain. Furthermore, the number of cups of coffee consumed or caffeine intake showed no significant correlation with acute and subacute pain.Conclusions Compared with nondrinkers, heavy daily coffee drinkers may be more likely to have chronic pain, but it is affected by multiple factors. Basic research and prospective clinical studies are needed to further determine the causality in this association.

-

Keywords:

- acute pain /

- subacute pain /

- chronic pain /

- coffee /

- caffeine /

- cross-sectional study

-

主编:Deepak L. Bhatt

出版商:Elsevier

心脏导管和介入术自20世纪上半叶由德国外科医生福斯曼发明以来, 逐步发展和完善, 已经成为当代心脏病学的基石。该领域的技术已从简单的压力测量、描记曲线, 发展为心血管疾病明确诊断、完成治疗不可或缺的手段。很多风险高、创伤大的外科手术已被微创、低风险的介入治疗所取代,医疗经济效益比因此显著提高。如今,心血管介入领域的设备器材、诊疗程序和技术仍在日新月异地发展,如何不断更新和提高介入技术水平,面对不同患者作出最正确的介入临床决策,是心血管医师面临的极大挑战。本书由著名的心血管介入专家Bhatt博士负责组织编写,全面系统地介绍了心血管介入各个领域的最新诊断和治疗策略,以及相关介入技术的原理和要点。

本书分为7部分。第1部分介绍心脏介入治疗的指南、辅助药物和周边技术。第2部分则具体论述冠状动脉介入手术中的难点如无保护左主干病变、慢性完全闭塞病变、分叉病变、桥血管、支架内再狭窄、血栓病变等的处理,以及血管内成像技术的操作、应用和进展。第3部分是外周血管介入,分别阐述上下肢动脉、肾动脉、肠系膜动脉及胸腹主动脉瘤等病变处理技巧,此外还涉及了最新的肾动脉去交感神经术。第4部分脑血管介入术,分为颈、椎动脉和颅内动脉介入两部分。第5部分为静脉系统介入治疗,包括下肢深静脉血栓和肺栓塞的处理,慢性深静脉功能不全及血液透析动静脉瘘通路的处理。第6部分是结构性心脏病的介入诊疗,包括主动脉瓣成型术和经导管主动脉瓣置换术,经导管二尖瓣介入术,肥厚型心肌病、卵圆孔未闭、房间隔缺损及室间隔缺损的封堵,心内膜活检和心包穿刺及介入治疗。最后一部分简要介绍了其他先天性心脏病如主动脉缩窄、动静脉瘘畸形等的介入策略。

心脏介入学是一个操作性、可视性极强的学科,本书充分体现了这一特点。其包含431幅彩图和116个图表,直观、清晰地阐述了诊治流程和介入操作中的关键所在,相应网站上的视频和动画更方便于学习和知识更新。因此,作为Braunwald心脏病学伴侣系列丛书中的一本,本书不仅适用于从事心血管介入或接受心血管介入专科培训的医生,对放射科介入医生、心血管外科医生和经常与介入医生密切合作的其他心血管医生都有很好的参考作用,是一本不可多得的实用性极强的心血管介入参考书。

(北京协和医院心内科 郭潇潇)

(中国医学科学院图书馆 供 稿)

作者贡献:闻蓓负责研究设计、数据处理、论文撰写;朱贺负责数据提取、图表绘制;许力、黄宇光负责研究设计、论文修订与审核。利益冲突:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突 -

表 1 13 428名受试者一般临床资料

Table 1 General characteristics of 13 428 participants

指标 纳入人群数量

[n(%)]权重估算人群数量(n) 权重估算人群百分比

[%(95% CI)]年龄(岁) 20~<45 5943(44.3) 95 354 579 50(49~51) 45~<60 2764(20.6) 51 491 472 27(26~28) ≥60 4721(35.2) 43 863 106 23(22~23) 性别 男 6366(47.4) 91 540 395 48(47~49) 女 7062(52.6) 99 168 762 52(51~53) 种族 墨裔美籍人 3023(22.5) 13 349 641 7(7~8) 其他西班牙裔 613(4.6) 11 442 550 6(5~6) 非西班牙裔白人 6774(50.4) 137 310 593 72(71~73) 非西班牙裔黑人 2552(19.0) 20 978 007 11(10~11) 其他 466(3.5) 7 628 366 4(4~5) 受教育程度 高中以下 4341(32.3) 38 713 959 20(20~21) 高中 3179(23.7) 49 775 090 26(25~27) 高中以上 5882(43.8) 102 029 399 54(52~55) 缺失 26(0.2) - - 婚姻状态 已婚 7310(54.4) 106 797 128 56(55~57) 丧偶 1325(9.9) 11 442 549 6(6~7) 离异 1144(8.5) 17 163 824 9(9~10) 分居 426(3.2) 5 721 275 3(2~3) 单身 2047(15.2) 30 513 465 16(16~17) 同居 708(5.3) 11 442 549 6(5~6) 缺失 468(3.5) - - PIR <1.3 3502(26.1) 38 141 831 20 (19~21) 1.3~<1.8 1468(10.9) 17 163 824 9(8~10) ≥1.8 7309(54.4) 122 053 860 64(63~65) 缺失 1149(8.6) - - 每天饮酒情况(杯) 0 4146(30.9) 51 491 472 27(26~28) 1~2 5755(42.9) 85 819 121 45(44~46) >2 2867(21.4) 45 770 198 24(23~25) 缺失 660(4.9) - - 体质量指数(kg/m2) <20 628(4.7) 9 535 458 5(5~6) 20~<25 3523(26.2) 53 398 564 28(28~30) 25~<30 4697(35.0) 64 841 113 34(33~35) ≥30 4212(31.4) 57 212 747 30(29~31) 缺失 368(2.7) - - 日常体力活动 久坐 3445(25.7) 47 677 289 25(24~26) 轻度体力活动 7076(52.7) 95 354 579 50(49~52) 中度体力活动 2032(15.1) 32 420 557 17(16~18) 重度体力活动 859(6.4) 13 349 641 7(7~8) 缺失 16(0.1) - - 吸烟 6506(48.5) 95 354 579 50 (49~51) 糖尿病 1646(12.3) 17 163 824 9(8~9) 每日咖啡因摄入(mg) 0 7794(58.0) 106 797 128 56(55~57) >0~200 3152(23.5) 40 048 923 21 (20~22) >200 2482(18.5) 43 863 106 23 (22~24) 每日咖啡摄入(杯) 0 7794(58.0) 106 797 128 56(55~57) >0~2 2077(15.5) 26 699 282 14 (13~14) >2 3557(26.5) 57 212 747 30 (29~31) 疼痛 无疼痛或疼痛持续时间<24 h 10 202(76.0) 139 217 685 73(72~74) 急性疼痛 910(6.8) 15 256 732 8(8~9) 亚急性疼痛 369(2.7) 5 721 275 3(3~4) 慢性疼痛 1947(14.5) 30 513 465 16(15~17) -:不适用;PIR(poverty-income ratio):贫穷比率 表 2 咖啡摄入与疼痛关系的无序多分类Logistic回归分析结果

Table 2 Results of multinomial Logistic analysis on the associations between coffee consumption and pain

疼痛类型 模型* 咖啡摄入杯数与疼痛的关系(以不摄入咖啡为参照) 咖啡因摄入与疼痛的关系(以不摄入咖啡因为参照) ≤2杯/d >2杯/d ≤200 mg/d >200 mg/d OR(95% CI) P值 OR(95% CI) P值 OR(95% CI) P值 OR(95% CI) P值 急性疼痛 模型1 0.941(0.735~1.206) 0.631 0.936(0.775~1.132) 0.497 0.925(0.751~1.140) 0.465 0.951(0.770~1.175) 0.643 模型2 1.090(0.846~1.405) 0.503 0.942(0.774~1.147) 0.550 1.038(0.838~1.287) 0.731 0.939(0.754~1.169) 0.572 模型3 1.079(0.833~13.96) 0.566 0.909(0.743~1.112) 0.355 1.031(0.829~1.282) 0.784 0.896(0.716~1.121) 0.336 亚急性疼痛 模型1 0.812(0.526~1.255) 0.3499 0.986(0.741~1.312) 0.923 0.801(0.562~1.420) 0.220 1.058(0.774~1.446) 0.723 模型2 0.840(0.545~1.294) 0.428 0.943(0.697~1.276) 0.705 0.808(0.565~1.154) 0.241 1.011(0.724~1.412) 0.949 模型3 0.870(0.572~1.327) 0.518 0.963(0.706~1.312) 0.810 0.845(0.593, 1.205) 0.353 1.018(0.724~1.433) 0.917 慢性疼痛 模型1 0.968(0.809~1.158) 0.720 1.354(1.187~1.544) <0.001 1.088(0.938~1.261) 0.266 1.372(1.185~1.587) <0.001 模型2 0.948(0.789~1.139) 0.568 1.243(1.083~1.427) 0.002 1.049(0.902~1.220) 0.537 1.249(1.072~1.456) 0.004 模型3 0.891(0.738~1.075) 0.228 1.125(0.975~1.297) 0.106 0.996(0.852~1.164) 0.960 1.103(0.941~1.293) 0.227 *模型1未对任何协变量进行校正,模型2仅对年龄、性别、种族进行校正,模型3对11个协变量均进行校正 表 3 咖啡摄入与慢性疼痛关系的无序多分类Logistic回归分析结果

Table 3 Results of multinomial Logistic analysis on the associations between coffee consumption and chronic pain

指标 以每日咖啡因摄入量为主变量 以每日咖啡摄入杯数为主变量 OR(95% CI) P值 OR(95% CI) P值 年龄(以20~<45岁为参照) 45~<60岁 1.291(1.096~1.520) 0.002 1.287(1.093~1.516) 0.003 ≥60岁 0.882(0.740~1.052) 0.161 0.887(0.744~1.058) 0.183 性别(以男性为参照) 1.384(1.209~1.584) <0.001 1.387(1.212~1.587) <0.001 种族(以墨裔美籍人为参照) 其他西班牙裔 1.737(1.241~2.432) 0.001 1.769(1.263~2.478) <0.001 非西班牙裔白人 2.528(2.079~3.073) <0.001 2.516(2.071~3.056) <0.001 非西班牙裔黑人 1.773(1.436~2.190) <0.001 1.776(1.438~2.194) <0.001 其他 2.009(1.423~2.836) <0.001 2.023(1.432~2.857) <0.001 受教育程度(以高中以下为参照) 高中 0.916(0.771~1.087) 0.314 0.914(0.77~1.084) 0.302 高中以上 0.787(0.666~0.928) 0.005 0.785(0.665~0.927) 0.004 婚姻状态(以已婚为参照) 丧偶 0.792(0.632~0.992) 0.042 0.791(0.632~0.991) 0.042 离异 1.154(0.944~1.410) 0.162 1.149(0.940~1.404) 0.176 分居 0.866(0.610~1.230) 0.421 0.869(0.612~1.235) 0.434 单身 0.627(0.506~0.777) <0.001 0.627(0.506~0.778) <0.001 同居 1.154(0.883~1.508) 0.293 1.153(0.883~1.506) 0.296 PIR(以<1.3为参照) 1.3~<1.8 0.914(0.738~1.132) 0.409 0.917(0.741~1.135) 0.427 ≥1.8 0.636(0.544~0.743) <0.001 0.633(0.541~0.739) <0.001 饮酒(以0杯/d为参照) 1~2杯/d 1.010(0.866~1.177) 0.902 1.009(0.865~1.176) 0.911 >2杯/d 0.916(0.750~1.118) 0.387 0.914(0.749~1.116) 0.377 体质量指数(以<20 kg/m2为参照) 20~<25 kg/m2 1.000(0.734~1.364) 0.998 1.001(0.734~1.364) 0.997 25~<30 kg/m2 1.261(0.927~1.714) 0.139 1.263(0.929~1.716) 0.137 ≥30 kg/m2 1.642(1.21~2.229) 0.002 1.644(1.212~2.231) 0.001 日常体力活动(以久坐为参照) 轻度体力活动 0.787(0.683~0.908) 0.001 0.786(0.682~0.906) <0.001 中度体力活动 0.839(0.692~1.018) 0.075 0.839(0.692~1.017) 0.074 重度体力活动 0.953(0.726~1.253) 0.732 0.950(0.723~1.249) 0.715 吸烟 1.707(1.494~1.950) <0.001 1.700(1.488~1.942) <0.001 糖尿病 1.443(1.199~1.735) <0.001 1.442(1.198~1.734) <0.001 每日咖啡因摄入量(以不摄入咖啡因为参照) >0~200 mg 0.996(0.852~1.164) 0.960 - - >200 mg 1.103(0.941~1.293) 0.227 - - 每日咖啡摄入杯数(以不摄入咖啡为参照) >0~2杯 - - 0.891(0.738~1.075) 0.228 >2杯 - - 1.125(0.975~1.297) 0.106 PRP:同表 1;-:不适用 -

[1] Watkins E A, Wollan P C, Melton L J 3rd, et al. A population in pain: report from the Olmsted County health study[J]. Pain Med, 2008, 9(2): 166-174. DOI: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00280.x

[2] Padfield D, Zakrzewska J M. Encountering pain[J]. Lancet, 2017, 389(10075): 1177-1178. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30756-0

[3] Treede R D, Rief W, Barke A, et al. Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: the IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11)[J]. Pain, 2019, 160(1): 19-27. DOI: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001384

[4] Gerrits M M J G, Vogelzangs N, Van Oppen P, et al. Impact of pain on the course of depressive and anxiety disorders[J]. Pain, 2012, 153(2): 429-436. DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.11.001

[5] Cornelis M C. Coffee intake[J]. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci, 2012, 108: 293-322.

[6] Abalo R. Coffee and caffeine consumption for human health[J]. Nutrients, 2021, 13(9): 2918. DOI: 10.3390/nu13092918

[7] Carrillo J A, Benitez J. Clinically significant pharmaco-kinetic interactions between dietary caffeine and medications[J]. Clin Pharmacokinet, 2000, 39(2): 127-153. DOI: 10.2165/00003088-200039020-00004

[8] Zylka M J. Needling adenosine receptors for pain relief[J]. Nat Neurosci, 2010, 13(7): 783-784. DOI: 10.1038/nn0710-783

[9] Chen Y H, Chou Y H, Yang T Y, et al. The effects of frequent coffee drinking on female-dominated healthcare workers experiencing musculoskeletal pain and a lack of sleep[J]. J Pers Med, 2022, 13(1): 25. DOI: 10.3390/jpm13010025

[10] Milde-Busch A, Straube A, Heinen F, et al. Identified risk factors and adolescents' beliefs about triggers for headaches: results from a cross-sectional study[J]. J Headache Pain, 2012, 13(8): 639-643. DOI: 10.1007/s10194-012-0489-7

[11] Aggarwal N, Anand T, Kishore J, et al. Low back pain and associated risk factors among undergraduate students of a medical college in Delhi[J]. Educ Health (Abingdon), 2013, 26(2): 103-108. DOI: 10.4103/1357-6283.120702

[12] Lehmann S, Milde-Busch A, Straube A, et al. How specific are risk factors for headache in adolescents? Results from a cross-sectional study in Germany[J]. Neuropediatrics, 2013, 44(1): 46-54. DOI: 10.1055/s-0032-1333432

[13] Nouri-Majd S, Salari-Moghaddam A, Hassanzadeh Keshteli A, et al. Coffee and caffeine intake in relation to symptoms of psychological disorders among adults[J]. Public Health Nutr, 2022, 25(12): 1-28.

[14] Boppana S H, Peterson M, Du A L, et al. Caffeine: what is its role in pain medicine?[J]. Cureus, 2022, 14(6): e25603.

[15] Bagó-Mas A, Korimová A, Deulofeu M, et al. Polyphenolic grape stalk and coffee extracts attenuate spinal cord injury-induced neuropathic pain development in ICR-CD1 female mice[J]. Sci Rep, 2022, 12(1): 14980. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-022-19109-4

[16] Johnson C L, Paulose-Ram R, Ogden C L, et al. National health and nutrition examination survey: analytic guidelines, 1999—2010[J]. Vital Health Stat 2, 2013, 161: 1-24.

[17] Riskowski J L. Associations of socioeconomic position and pain prevalence in the United States: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey[J]. Pain Med, 2014, 15(9): 1508-1521. DOI: 10.1111/pme.12528

[18] Niezen S, Mehta M, Jiang Z G, et al. Coffee consumption is associated with lower liver stiffness: a nationally representa-tive study[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2022, 20(9): 2032-2040.e6. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.09.042

[19] Douketis J D, Paradis G, Keller H, et al. Canadian guidelines for body weight classification in adults: application in clinical practice to screen for overweight and obesity and to assess disease risk[J]. CMAJ, 2005, 172(8): 995-998. DOI: 10.1503/cmaj.045170

[20] Wang Y, Zhu Y H, Chen Z B, et al. Association between electronic cigarettes use and whole blood cell among adults in the USA-a cross-sectional study of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey analysis[J]. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int, 2022, 29(59): 88531-88539. DOI: 10.1007/s11356-022-21973-6

[21] American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes-2021[J]. Diabetes Care, 2021, 44(Suppl 1): S15-S33.

[22] Perdomo C M, Cohen R V, Sumithran P, et al. Contemporary medical, device, and surgical therapies for obesity in adults[J]. Lancet, 2023, 401(10382): 1116-1130. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02403-5

[23] Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, et al. Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain among adults-United States, 2016[J]. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2018, 67(36): 1001-1006.

[24] Nieber K. The impact of coffee on health[J]. Planta Med, 2017, 83(16): 1256-1263. DOI: 10.1055/s-0043-115007

[25] Caporaso N, Whitworth M B, Grebby S, et al. Non-destructive analysis of sucrose, caffeine and trigonelline on single green coffee beans by hyperspectral imaging[J]. Food Res Int, 2018, 106: 193-203. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodres.2017.12.031

[26] Fredholm B B. Notes on the history of caffeine use[J]. Handb Exp Pharmacol, 2011, 200: 1-9.

[27] Fredholm B B, Yang J, Wang Y. Low, but not high, dose caffeine is a readily available probe for adenosine actions[J]. Mol Aspects Med, 2017, 55: 20-25. DOI: 10.1016/j.mam.2016.11.011

[28] Derry C J, Derry S, Moore R A. Caffeine as an analgesic adjuvant for acute pain in adults[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2012, 2012(3): CD009281.

[29] García-Blanco T, Dávalos A, Visioli F. Tea, cocoa, coffee, and affective disorders: vicious or virtuous cycle?[J]. J Affect Disord, 2017, 224: 61-68. DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.11.033

[30] Caldwell A R, Tucker M A, Butts C L, et al. Effect of caffeine on perceived soreness and functionality following an endurance cycling event[J]. J Strength Cond Res, 2017, 31(3): 638-643. DOI: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000001608

[31] Halker R B, Demaerschalk B M, Wellik K E, et al. Caffeine for the prevention and treatment of postdural puncture headache: debunking the myth[J]. Neurologist, 2007, 13(5): 323-327. DOI: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e318145480f

[32] Liang J F, Wang S J. Hypnic headache: a review of clinical features, therapeutic options and outcomes[J]. Cephalalgia, 2014, 34(10): 795-805. DOI: 10.1177/0333102414537914

[33] Scher A I, Stewart W F, Lipton R B. Caffeine as a risk factor for chronic daily headache: a population-based study[J]. Neurology, 2004, 63(11): 2022-2027. DOI: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000145760.37852.ED

[34] Chan W S, Levsen M P, Puyat S, et al. Sleep discrepancy in patients with comorbid fibromyalgia and insomnia: demographic, behavioral, and clinical correlates[J]. J Clin Sleep Med, 2018, 14(11): 1911-1919. DOI: 10.5664/jcsm.7492

[35] Trouvin A P, Attal N, Perrot S. Lifestyle and chronic pain: double jeopardy?[J]. Br J Anaesth, 2022, 129(3): 278-281. DOI: 10.1016/j.bja.2022.06.006

[36] Chen D X, Yang H Z, Yang L, et al. Preoperative psychological symptoms and chronic postsurgical pain: analysis of the prospective China Surgery and Anaesthesia Cohort study[J]. Br J Anaesth, 2024, 132(2): 359-371. DOI: 10.1016/j.bja.2023.10.015

[37] Schmid A A, Atler K E, Malcolm M P, et al. Yoga improves quality of life and fall risk-factors in a sample of people with chronic pain and Type 2 Diabetes[J]. Complement Ther Clin Pract, 2018, 31: 369-373. DOI: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.01.003

[38] Shaygan M, Yazdanpanah M. Prevalence and predicting factors of chronic pain among workers of petrochemical and petroleum refinery plants[J]. Int J Occup Environ Med, 2020, 11(1): 3-14. DOI: 10.15171/ijoem.2020.1632

[39] McVinnie D S. Obesity and pain[J]. Br J Pain, 2013, 7(4): 163-170. DOI: 10.1177/2049463713484296

-

期刊类型引用(3)

1. 刘慧丽,闻蓓,白雪,陈明安,李民. 体重校正腰围指数与疼痛的相关性:一项横断面研究. 北京大学学报(医学版). 2025(01): 178-184 .  百度学术

百度学术

2. 周永泰,杨朕钰,李岩,吴嘉静,赵波. LCN2在神经系统疾病中作用机制研究进展. 协和医学杂志. 2025(02): 330-337 .  本站查看

本站查看

3. 张宾,尹力为,朱欢欢,肖亮满,麦绮琪,叶颖蓝,庄礼兴. 基于雷达图再评价浮针治疗痛症的系统评价/Meta分析. 新疆医科大学学报. 2024(05): 746-754 .  百度学术

百度学术

其他类型引用(0)

作者投稿

作者投稿 专家审稿

专家审稿 编辑办公

编辑办公 邮件订阅

邮件订阅 RSS

RSS

下载:

下载: